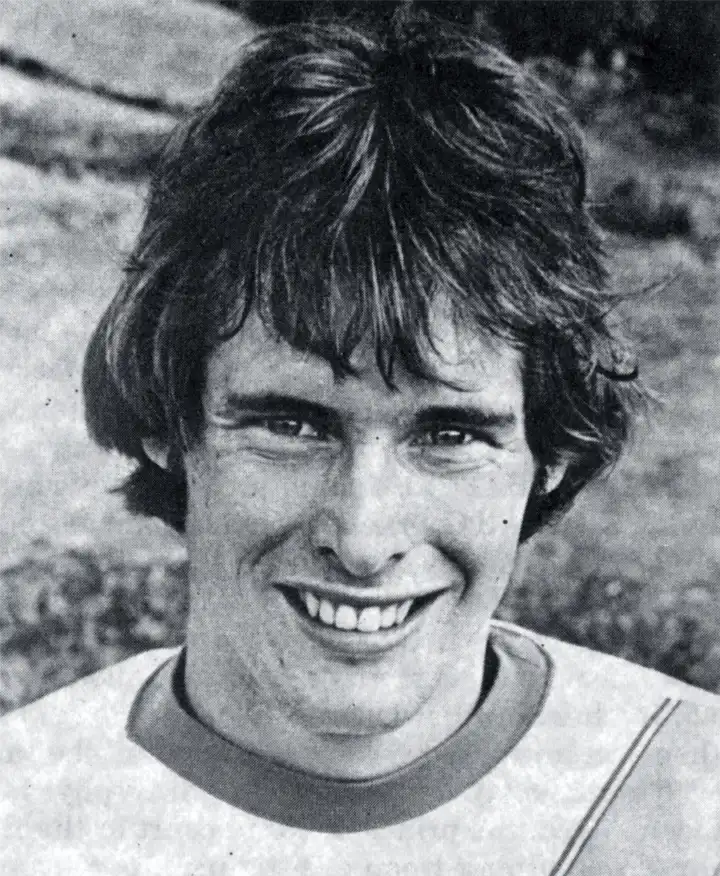

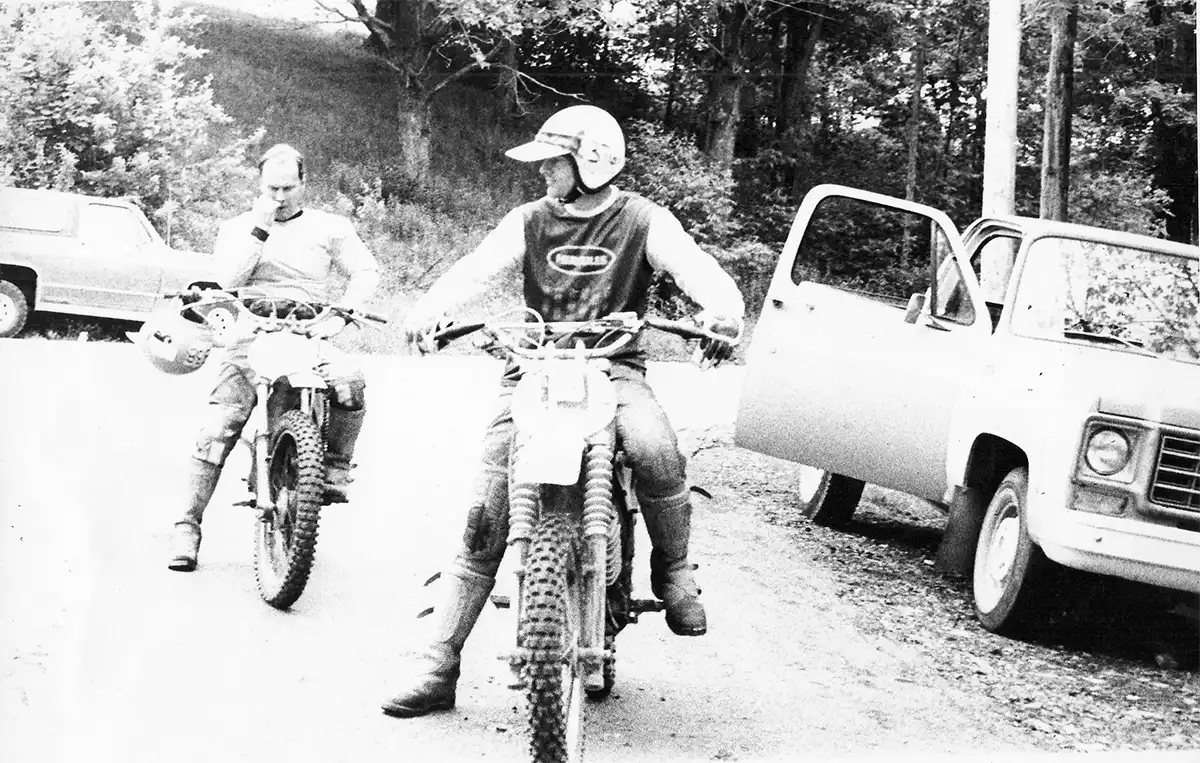

Bruce McDougal

METTCO PENTON

A Rider’s View

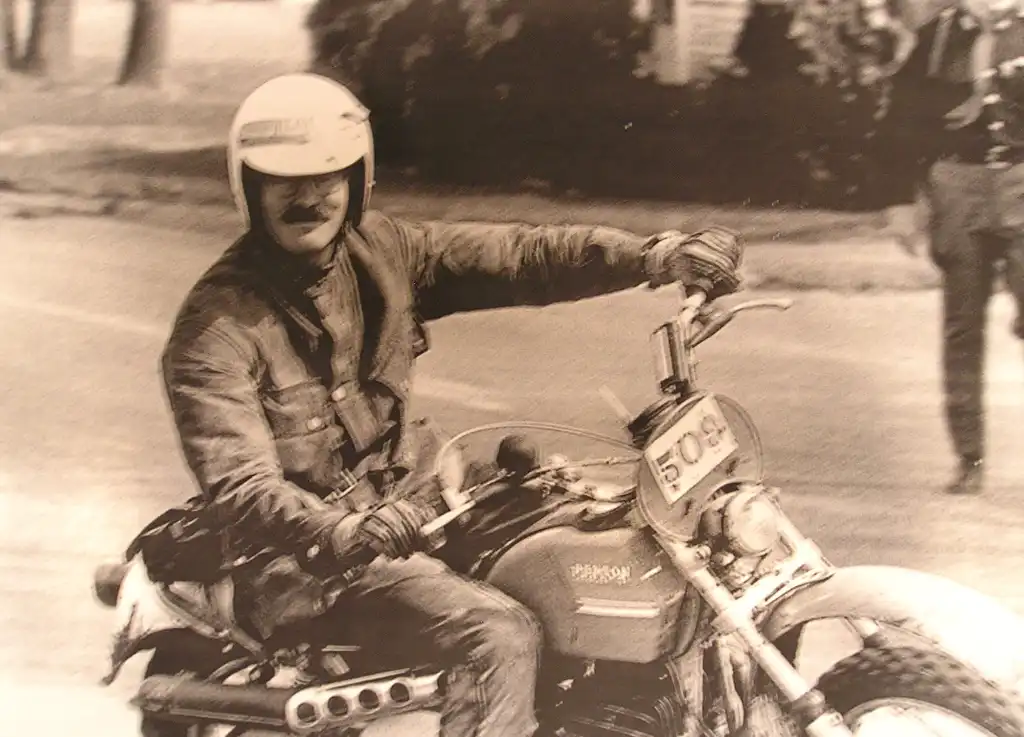

By Bruce McDougal

Originally published in the Fall 2005 issue #28 of "Still....Keeping Track"

I first became aware of Fred & Kay Hayes’ Mettco Pentons in 1972. I was 17 years old at the time, had just graduated high school, and was at a night motocross at El Toro Speedway, in El Toro, California.

Actually, to refer to El Toro’s course as a motocross track is stretching it a bit, as it consisted of a short track/TT oval, but with plywood ramps up the sides of the concrete outer walls, leading to some trails surrounding the place – and all with pretty poor lighting.

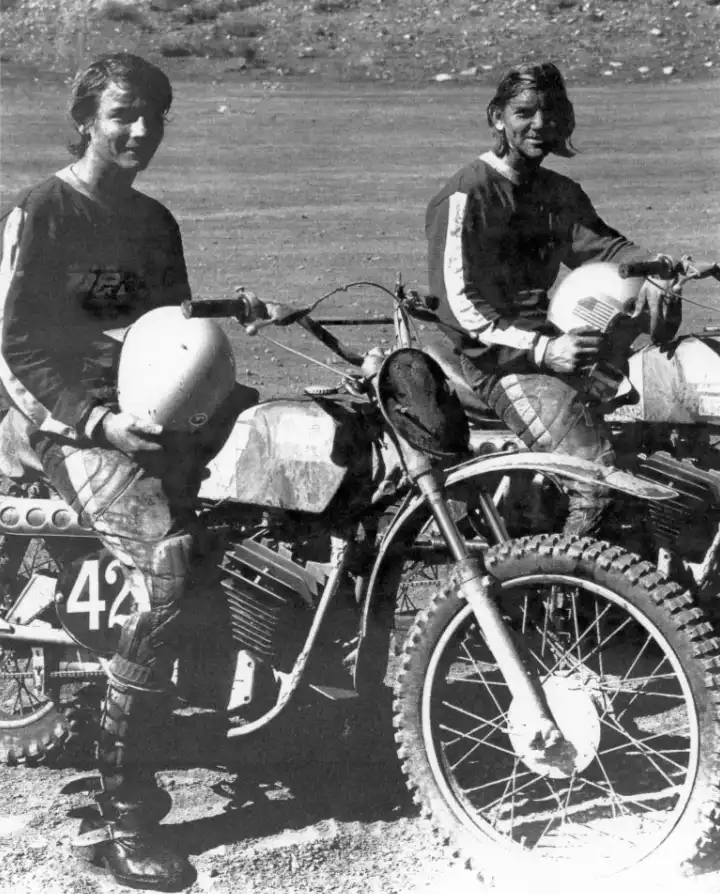

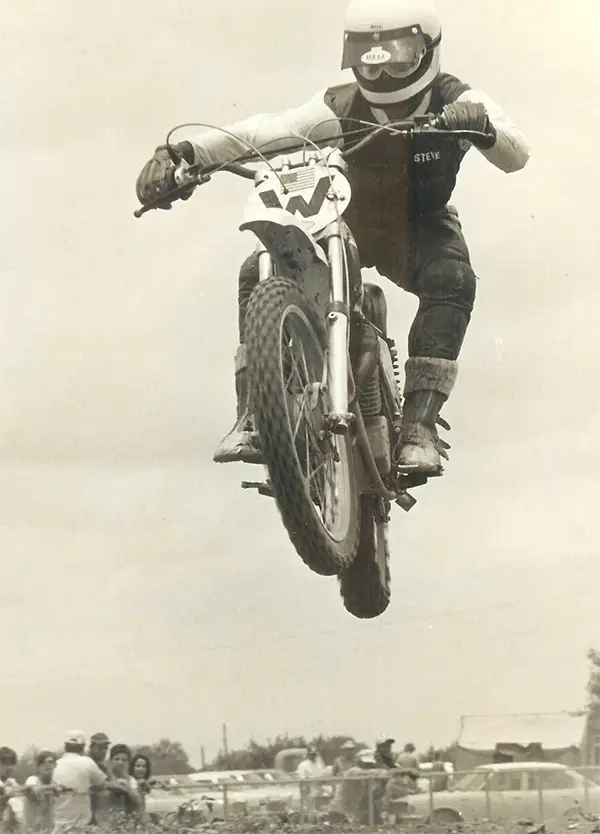

I was competing in the 125 class on a Yamaha AT1 and, with support from Yamaha International, also had National Champion Gary Jones’ 250 Yamaha from the previous season, for the 250 class. I was also doing some 500-class racing on a 250 Greeves Griffin, which was owned by Don Draco, of Draco Kawasaki, in Santa Ana, California. However, my friend Chuck Bower showed up with this 125 Penton, sponsored by Mettco Racing.

There were a lot of fast and talented riders competing at El Toro back then. Local pro’s such as Morris Malone, Bruce Baron, Davy Carlson, Gary Wells, Werner Schultz, and Dave Boysten, to name a few, made all the classes extremely competitive.

But on this night the clutch on my 250 Yamaha broke during practice. I had resigned myself to riding just the 125 class on my AT1, but then Chuck offered to let me ride his 125 Mettco Penton in the 250 class.

Before Chuck brought that Mettco Penton to El Toro, the only other times I had ever even seen a Penton were at Saddleback Park and Carlsbad, being ridden by guys like Gary Bailey, Lars Larson, Bill Silverthorn, and Ruben Benitez. Needless to say, I jumped at the chance to ride Chuck’s Penton.

Considering that I would be riding it in the 250 class, I was hoping just to keep the fast guys in sight. Well, much to my surprise, I ended up winning that race! After riding my 125 Yamaha AT1, the Penton was like riding a works bike.

Right after the event, I asked Chuck where Mettco Racing was located, and how much a Penton cost. I was ready to go right down there and sign on the dotted line. However, the next day, and before I even got the chance to go to the Mettco shop, Chuck called me and said that Fred Hayes was looking for another 125-class rider. I immediately went over to see Mr. Hayes before he could change his mind!

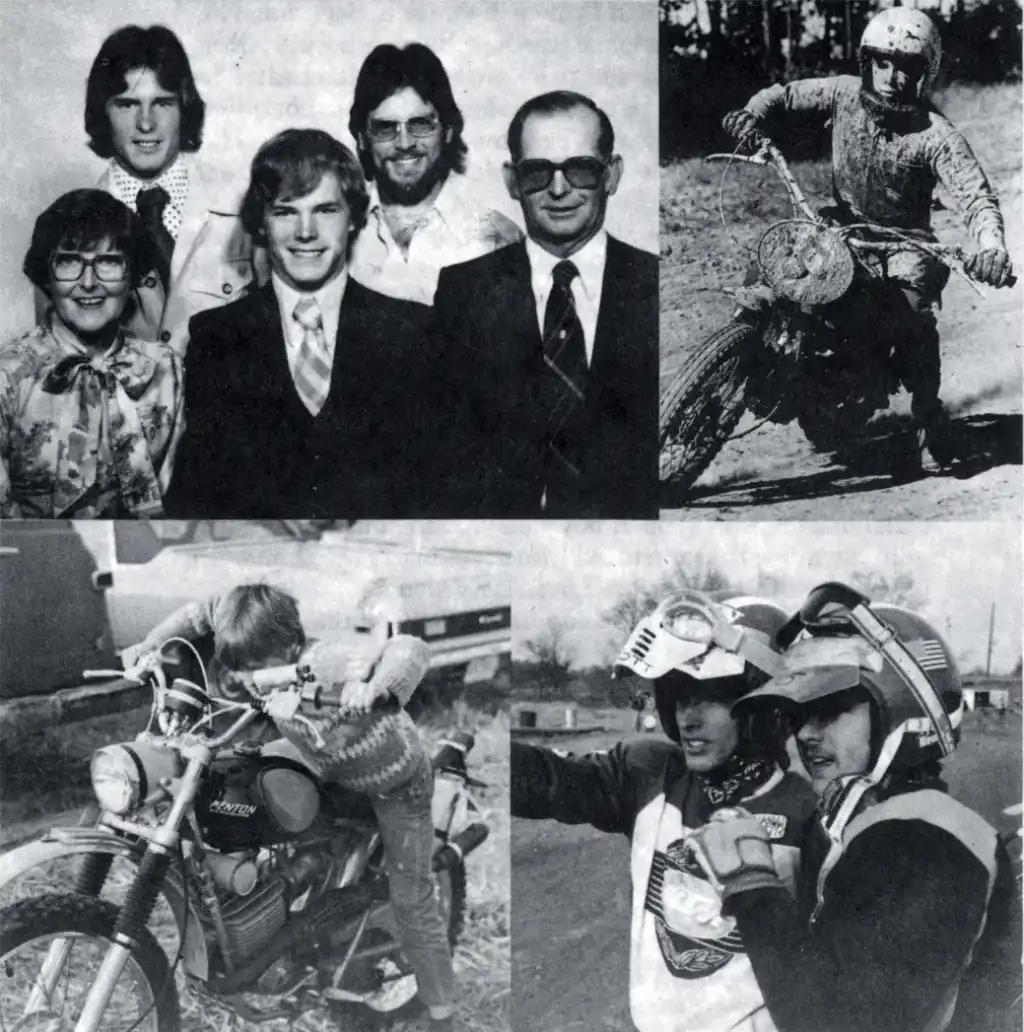

Once at Mettco, I met Fred and Kay Hayes, along with Fred’s parents. They were all very nice and made me feel right at home. And, before the day was over, I had become an employee of Mettco Racing, and a sponsored Mettco rider.

The very first race in which I competed on my own Mettco Penton was at Lions Dragway, near Ascot Park, in Long Beach, California. We would race there on Wednesday nights, then at Orange County Raceway on Thursday nights, Friday nights at Corona Raceway, Corona again on Saturday, or at Saddleback Park, then Carlsbad on Sunday.

This all was during the early days of motocross. The night races were poorly lit and often dusty. Most of the tracks didn’t have starting gates early on, either. Instead, we would start with the one-hand-on-the-helmet method, or with a rubber band. The rubber bands were just that. A giant rubber band was stretched across in front of the entire starting field, then it was let loose, snapping away from in front of the riders, and away we would go!

My Mettco Penton was extremely fast from day one, and with Fred’s ongoing R & D, just kept getting faster and faster. The bikes also handled great and were definitely ahead of their time in 1972. Among the modifications we used were porting, head work, shifting systems, re-laced wheels with DID rims & stainless steel spokes, and Bassani pipes. Plus, we pop-riveted the stock fuel tank’s seams, and ran a variety of different rear shocks, such as Curnutt, Koni, and Works Performance, and early on, experimented with Yamaha front hubs and brakes.

Fred and Kay Hayes, and Fred’s mother and father, were the hardest working, nicest, and most dedicated people I have ever worked for. They couldn’t do enough to help us in our efforts to win races. If there was anything we needed to further our chances to win, all we had to do was ask. They were there for us in every way possible.

Chuck and I, and later Danny LaPorte, competed all over Southern California, often choosing where to go by virtue of what track had the largest purse. We just kept winning on our Mettco Pentons, especially at the night races, which we tended to frequent. This was all before there was a 125 National Championship class, but while I was with Mettco, we did travel to St. Louis, Missouri to compete in a 125 GP, and rode a pre-championship 125 national, in Southern California.

Chuck and I both rode 125’s most of the time, but also raced Penton 250’s after they came out in 1973. However, before the 250’s were introduced, Chuck would compete on a 175 in the 250 class at night races. My brother, Bob, also did some racing for Mettco, riding a 100 Penton. Fred said that Bob’s 100cc Mettco Penton was by comparison the fastest bike in its class.

Soon, lots of Pentons began to show up at the races, especially Mettco Pentons. You could look down the starting line at 125-class races and see nothing but green Penton tanks, often making up some two-thirds of the fields. At most big 125 races and night races, it was rare not to see a Mettco jersey in the top five.

I continued to ride Mettco Pentons for Fred and Kay Hayes until the 1974 season, when I was offered a factory Honda ride, with which to compete in the Nationals – the first year for a 125 class. However, in my opinion, the last 125 Mettco Penton I competed on was faster than my works Honda.

Of course, that was all a long time ago. I’ve done a lot of racing since then, including several seasons of campaigning the nationals, and for different factory teams. Today however, more than thirty years later, I am back to competing on a 125 Mettco Penton.

My current bike is not an all-original Mettco bike, but it is fast, reliable, and extremely competitive in vintage 125-class racing. I also ride a modern bike – a big bore KTM four-stroke, but I really love my 125 Penton.

I have ridden and raced quite a few different brands of motorcycles over the last 40 years, but the Mettco Penton will always be my favorite. Racing it is still terrific fun, but I even enjoy just sitting and looking at it, remembering all the great times I have had (and continue to have!) racing Mettco Pentons.

I can sure understand why someone would want to restore a Mettco Penton and/or have one in their collection, but I myself couldn’t restore one and just let it sit there – I would have to ride it!

Several years ago I received my first phone call from someone in California inquiring about information to set-up a Mettco Penton bike. I had no idea what they were talking about. Since that time I received other inquiries. During a conversation with Bruce McDougal, I learned about some of the background of these bikes. Last year, I assigned Ted Guthrie the “task” of writing this story. Corresponding with Bruce and Mr. Hayes took longer than expected because of their busy work schedules. However, the delay was well worth the effort.

Alan Buehner

METTCO PENTON

By Ted Guthrie

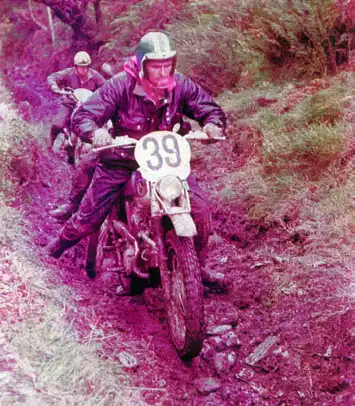

Penton motorcycles are often primarily associated with Eastern woods riding. After all, John Penton and his family call the state of Ohio home, and the image of a Penton motorcycle racing down a wooded trail is one most familiar with many enthusiasts of the brand.

However, it did not take long following introduction of the first Penton motorcycles, for riders from all over the country, as well as eventually the world, to discover just how well these machines performed, and in all kinds of competition.

Take California, for example. By the early 1970’s, motocross racing was really catching on throughout the state, with tracks opening up all over. Scores of riders were becoming involved, and there was a tremendous need for race-ready motocross machines.

Unfortunately, many of the bikes available at the time required considerable modification in order to perform well in motocross competition. Inadequate frames, poor suspension components, unreliable powerplants, and excessive weight, hampered many of the motorcycles of the era. Ah, but then Pentons were introduced to the motorcycling world.

Savvy riders and race shops recognized the tremendous advantages the bikes had to offer and pounced upon each and every one that was made available. One such shop, located in Compton, California, was called Mettco Racing.

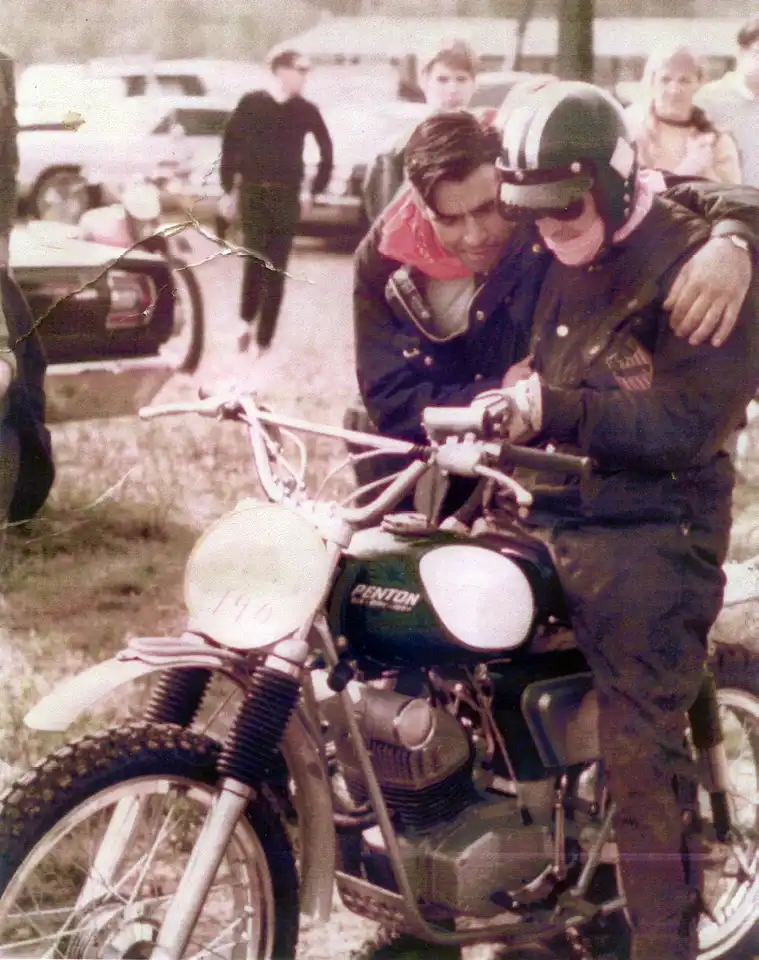

Fred Hayes opened Mettco, which stands for “Motocross, Enduro, Trail, and Trials, Competition Oriented”, in the early 1970’s, with the intention of catering to the ever-growing Southern California racing scene. Recognizing the potential of Penton motorcycles, Mr. Hayes set about building his business around them, but sold the Monark, Maico, and Saracens brands as well.

In addition to the retail motorcycle business, Fred also owned and operated Hayes Manufacturing, located right next to his race shop, which produced among other things, a variety of motorcycle parts and accessories. Included in those products were plastic number plates, mud flaps, and fork protectors.

However, Mr. Hayes’ passion, and what really brought attention to Mettco Penton, were the shop’s performance upgrades, offered both as bolt on parts, as well as complete high performance systems. Using powerful and reliable Penton motorcycles as a basis, Mr. Hayes offered various stages of what were referred to as Chuck Bower Specials.

Chuck, a local pro motocrosser and sponsored Mettco Penton rider, was making quite a name for himself at the time, wreaking havoc in Southern California 125-class racing. As a result, business was good at Mettco for such race-proven offerings as porting, head work, aluminum rims, stainless steel spokes, high-performance pipes, carbs, ignitions, straight cut gears, different shifting systems, and more.

Fred Hayes worked hard on these systems, continually testing and eval-uating their performance capabilities both on the track, as well as in the shop. In addition to Chuck Bower, Mettco riders Bruce McDougal, and Danny LaPorte, all provided valuable feedback from their racing efforts, while Mr. Hayes invested hundreds of hours running innumerable combinations of carbs, pipes, porting, and compression ratios, on his own dynometer.

Mr. Hayes relates that Mettco’s “secret” to success, is what wasn’t done to the bikes. That is, he chose not to make any radical changes, as did most of the other performance shops of the day. Instead, most of his engine modifications were based on the proven Sachs GS-series of engines.

A great admirer of John Penton, Mr. Hayes had the honor of accompanying John in 1973, on a trip to Europe. There he met with Freddie Stolberger, then the engine designer for KTM. The two men shared design philosophies, and from this, Mr. Hayes determined that by comparison, KTM’s factory racing engines produced more horsepower, but Mettco’s had a wider power band.

Back in the states, one of the most effective performance components developed by Mr. Hayes, were exhaust pipes. At first, Mettco Pentons used modified stock pipes with the ends removed, and a small silencer welded on. Later, pipes developed and produced by Darryl Bassani were used, which provided the Pentons with wider powerbands, and more top end speed.

However, as power and speed increased, there were some setbacks, such as failures of the stock connecting rods. Mr. Hayes overcame this problem by installing rods from 175cc engines. And, as a result of all these efforts, Mettco Pentons became faster, and their riders more and more successful.

Starting grids began to fill up with Pentons, some stock in appearance, some with the signature Mettco colors of white frames, black engines and hubs, and red tanks. Such was their success, that there was a time when two-thirds of many 125-class southern California motocross fields were made up of Pentons.

Fred Hayes’ influence, and contributions to the racing successes of Mettco, were not limited to machine preparation, either. He was also one of the early advocates of a training regimen for his riders. In fact, there were no details he would overlook in his efforts to support his team and to help his riders win. The result was that his “wrecking crew” of Bower, McDougal, and LaPorte were among the most successful riders in the highly competitive arena that was Southern California motocross racing in the early 1970’s.

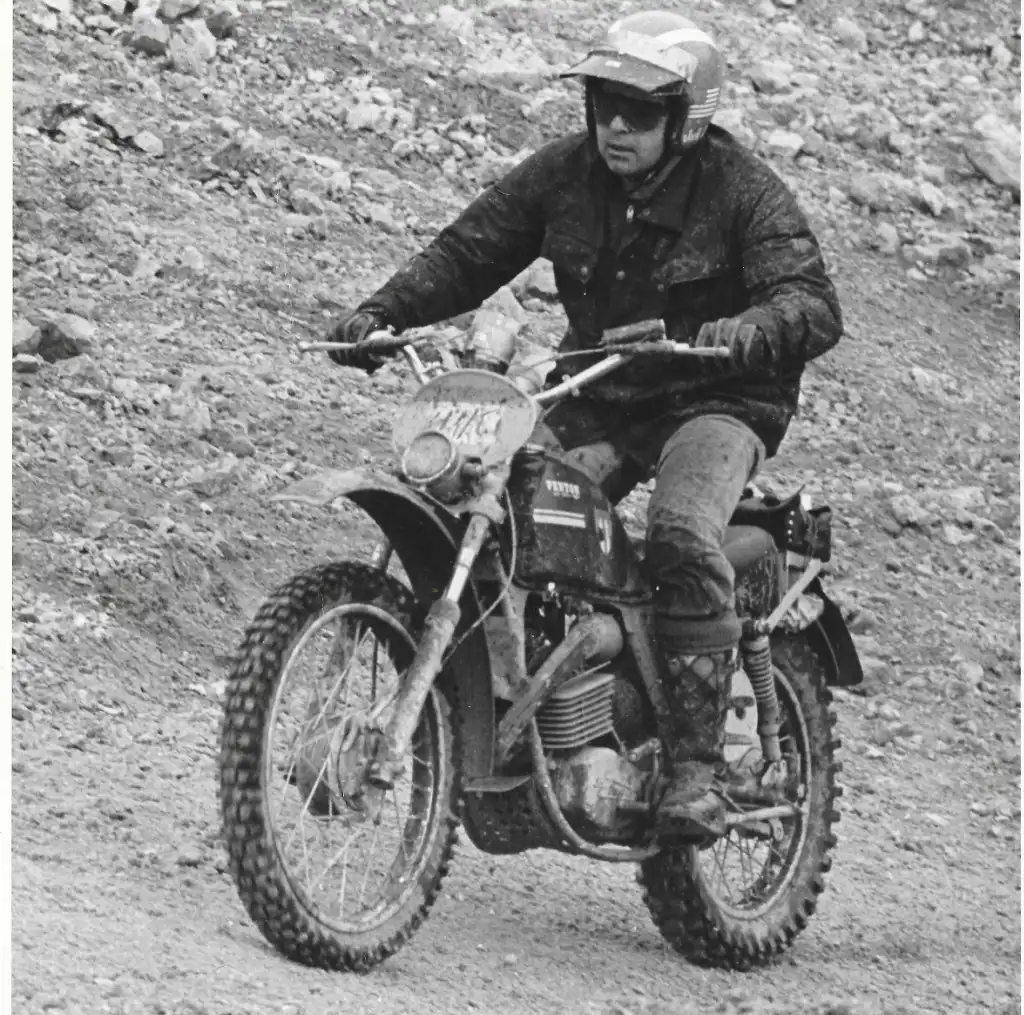

In addition to Mettco’s very successful motocross program, and as the company name implied, Mr. Hayes supported other forms of racing as well. Being an enduro rider and ISDT enthusiast himself, Fred sponsored a number of enduro riders, including Mike Adams, Carl Price, and Rick Munyon. And so it was that Fred Hayes and his small but extremely ambitious race shop set the standard for others to follow. The combination of Penton motorcycles’ capabilities and durability, along with Mr. Hayes’ insight, as well as his engineering and developmental efforts, his organizational and motivational abilities, and finally his foresight in hiring some very fast riders, resulted in racing and sales successes for the Penton brand, far from the wooded trails of Ohio.

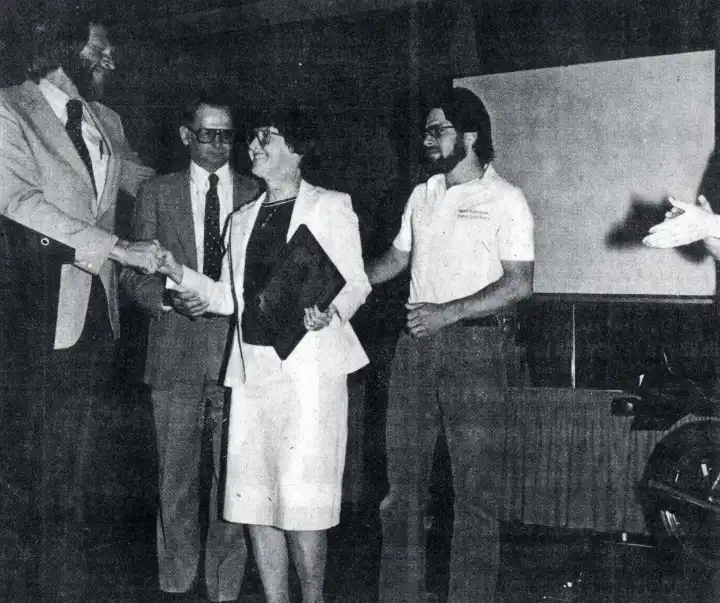

These days, Fred and Kay Hayes are as busy as ever, and continue to play a strong part in the motorcycle industry. However, unlike their Mettco racing efforts during the 1970’s, the Hayes have, in recent years been working to engineer, develop, and produce, a diesel-powered motorcycle, for use by the military.

While their present company, HDTUSA, has been supplying motorcycles to the U.S. military since 1982, this more recent project resulted in the world’s first purpose-built diesel motorcycle engine, for which Mr. Hayes finally secured a government contract, in the summer of 2005. And so, as back in the early 70’s when he was creating race-winning Pentons, Fred Hayes continues to improve and expand the capabilities of motorcycles with his special skills in engineering and development.

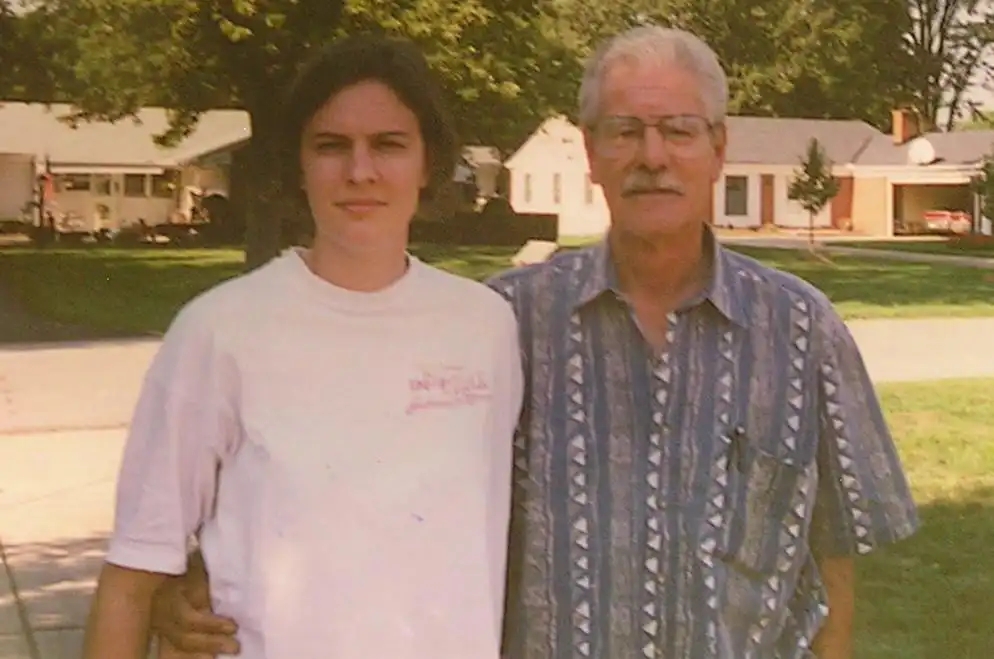

MY BROTHER TED: Dane Leimbach

Originally published in the Winter 2005 issue #29 of "Still....Keeping Track"

After being an only child for the first 71/2 years of my life, in February of '59, my parents had my first brother, and chose to call him Paul (after my Dad) Theodore (after mom's brother Ted). Because my father's name was also Paul, it was decided that Paul Theodore would be called Teddy, (and of course later, Ted) to keep the confusion in the household to a minimum.

Since there was such a large age difference between us, I wasn't too involved with Ted's life as a young child, simply because older brothers don't want to have anything to do with younger ones. That's just how life was. I'm sure we bonded as brothers and I do remember my mother telling me more than once, that both of my brothers (Orrin came along two years later) looked up to me and that I should behave in a manner that would be appropriate for a hero.

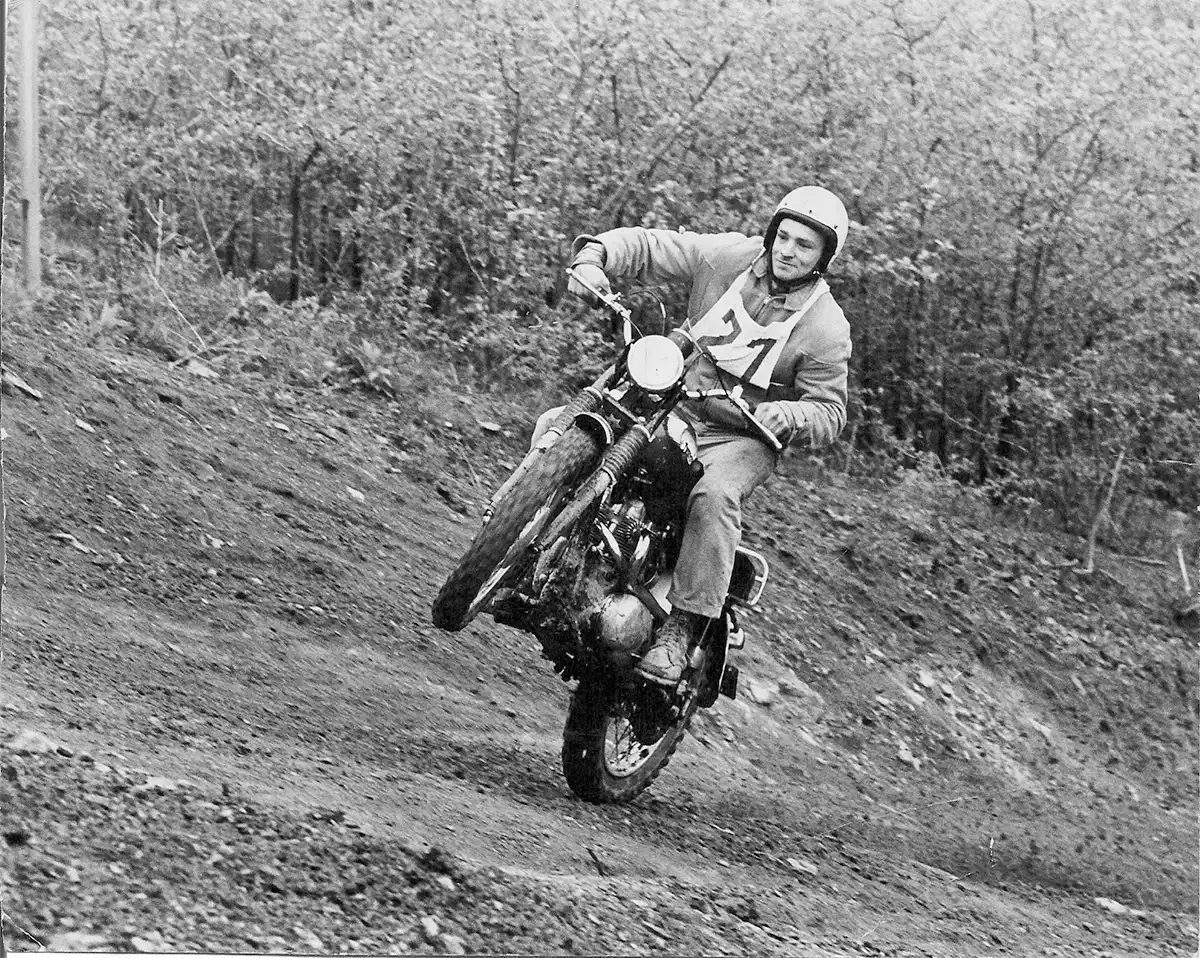

I got my first motorcycle when I was 16, a 100cc Penton Berkshire, and while this is another thing that I don't remember hearing about, I'm sure that my brothers were enamored by that wonderful piece of excitement. Since this time was way before the era when there were mini bikes, the brothers could just wish that they could ride my bike, and once in a while, I'd gift them with rides around the farm.

When Honda came out with their SL70 minicycle, the boys must have been hounding my parents unmercifully, because it wasn't too long after they appeared, that the boys ponied up the money from their savings to buy bikes for themselves. At first, they just rode them around the farm with one another, but eventually, they wanted to follow my footsteps and begin to race. The short part of the story is that Ted became a pretty accomplished rider, and became one of the targets for the other mini riders in the area, to beat at the local motocrosses.

As Ted grew, his riding skills developed and when he finally got big enough, Ted inherited one of my cast-off 100's, I think an ISDT bike from the previous year. I would have ridden the bike through the next Qualifier season, but then it was time for a new owner, and I believe that was Ted's first full size motorcycle.

Just as with the minicycles, Ted took to riding the 100 like a duck to water, and he forwarded his reputation as a winner in the local motocross scene. Since I was involved in the ISDT type events, and as my mother told me, my brothers looked up to me, Ted also wanted to become involved with those events as well. Once Ted started to ride the qualifiers, he quickly adapted his riding skills to that type of event, and once again, top placings came with some amount of ease.

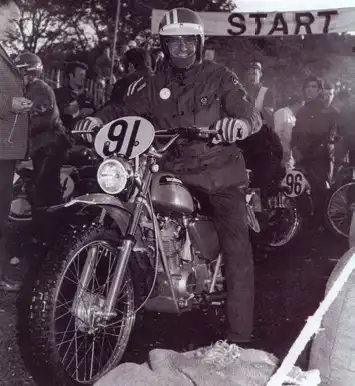

Our father was 5'10” tall and while I didn't seem to have inherited any of those height genes, Ted did. As he aged, he grew past me, and at some point, while I was still enjoying riding the smaller bikes, Ted decided that he wanted to begin to ride the bigger machines. In 1978, after the Penton era closed, Ted continued to ride bikes that were manufactured by KTM, and he became a very accomplished woods rider. His hare scramble skills, carved out of his ISDT qualifier riding, made him one of the prime candidates for overalls whenever he rode a local event. Ted's first ISDT was the Swedish event in 1978, and I believe that he earned a gold medal in that event.

Ted continued to ride the KTM's through the 1979 season and toward the end of that year, Jack Penton, who had signed a contract with Kawasaki Motors Corporation to run an enduro program for them, signed Ted to a contract to ride for him on Kawasaki's. Again that season, Ted managed to qualify for the ISDT in Brioude, France, and was looking forward to riding on the US team in the ISDT.

At this time in my riding career, I had been riding for over 10 years, and the drive for me to continue riding, was being fueled by Ted's success. I enjoyed teaching him the nuances of woods riding and playing the games that it took to finish well in the ISDT events.

Outside of the motorcycle world, Ted was still a farm boy, growing up on the “End O' Way” farm. Until I graduated from high school, I worked for Dad on the farm, as did both Orrin and Ted. During the summer of 1970, I went to work for Uncle Ted (Penton), and that led me further into the motorcycle world. I attended Wilmington College for two years before going to work for Penton Imports full time in the summer of 1972.

Because of the direction my career path took, my mother and father realized that if they wanted one of their heirs to continue to run the “End O' Way, they would have to change the way that they looked at the boys. Instead of just being their children, they sat down and made them partners in the farm. Despite Ted's love of motorcycle riding, he really liked the farm work and as a result, he was headed in the direction of being the next generation farmer in the family. While Orrin could do the work, Ted really took to it with a passion. He espoused my father's work ethic, and just like my dad, Ted would be hard at it until the farm work was finished for the day.

Once Ted and Orrin graduated from high school, they both followed my father's footsteps to The Ohio State University. Ted got wrapped up in the agriculture program and Orrin, who was more of a deep thinker, headed into computer studies. Ted continued to ride while he was attending school, though it did take a bite out of his riding time.

It seems that every family has one child that has a social streak that is stronger than other children, and in our family that was Ted. As he got into high school, he became a very popular guy, and seemed to be in the right time and place to party. I don't remember him getting into any major troubles, but he did know how to have a good time. I do remember that one time, long after the fact, my folks found some proof that Ted had held a pretty comprehensive party at our house. Dad was cleaning out the well, which was in front of the house, and down in the well he found a half dozen or so beer cans, that he was pretty sure he'd not thrown down the well.

Not only did he know how to have a good time, the girls seemed to take a real fancy to him as well. So with his good nature, party skills, and good looks, it wasn't hard for Ted to have a few girls chasing him much of the time. But because of the riding thing that took up much of his time, he never had a long time relationship that steered him from the motorcycle world.

At the end of the summer of 1980 as we were getting ready to go to the ISDT in Brioude, France, things changed forever in all of our lives. One afternoon, we were working on the bikes at our shop in Lorain, Ohio, and a strong thundershower blew through the area. It didn't last long but long enough to put down some heavy rain. Just as the rain was ending, we heard a number of emergency vehicles rush past our shop, up to the intersection two blocks away, and turn down under the railroad underpass. We really didn't take much notice because the shop was two blocks from St. Joseph's Hospital with their ambulance service and two blocks away from one of Lorain's fire stations. We were used to hearing the sirens from emergency vehicles all the time.

Not too long after we heard the emergency vehicles rush in that direction, we got a call at the shop, from my parents, that Ted was in a terrible accident, and he was in St. Joe's intensive care unit.

Ted had finished working at home on the farm that day, and was going to come to the shop to work on his Six Day bike. After he stopped at the shop to “check in”, he decided that he needed to go over the “high level bridge” to McDonalds to get something to eat. As he was returning, that was when the thundershower struck, and there was a small river of water running down the bridge and across all four lanes from the roadway as it exited the bridge. When Ted came down off the bridge and hit the water, his Ford Festiva hydroplaned and slid into the path of an oncoming truck. Even though Ted was wearing his seat belt, he hit his head on the door post and was knocked unconscious along with severely breaking his left leg.

The EMT's got him to the hospital and the ER doc's fixed him up as best they could, but he still didn't regain consciousness, so all we could do was wait and see what happened next.

The ISDT was coming up in two weeks. The rest of us had to leave to go to France to compete and my parents both felt that it was best that I go, because they were pretty sure that is what Ted would have wanted.

On the morning of the first day, when Ted was to have started the ISDT, he passed away as the result of complication from an embolism in his neck. It will go without explanation, that was the absolutely most difficult time in my life. Not only had I just lost a brother, but I had just lost the drive in my life in motorcycling. That day, my KDX 125 that we had built specially for the ISDT gave up on me that first morning, and I DNF'd my last ISDT.

The next spring, I tried to get back into riding again, but when we got to the first ISDT qualifier at the Zink Ranch in Oklahoma, I just couldn't do it. There was just no drive to ride a motorcycle any more, because I'd lost my inspiration.

Even though there was such an age difference between us, I was as close to Ted as any brothers would be. Once he got into the motorcycle world, we became even closer, because I enjoyed watching him learn about the sport that I'd adopted as my passion and vocation. He was a great person who never got to realize his place in life and was not able to contribute everything to our lives, but will always be fondly remembered.

An interview with Matt Weisman: by Alan Buehner

Originally published in the Winter 2002 issue #17 of "Still....Keeping Track"

Anyone that has seen a “PENTON” motorcycle ad in one of the “old” magazines has experienced a small part of Matt Weisman’s talent and the vital role that he played in working for John Penton from 1969 thru 1986. He created all of the Penton Motorcycle and Hi-Point print media advertising, as well as all of the dealer and consumer literature, such as “Keeping Track” newsletters, service manuals and parts catalogs. He maintained the dealer and consumer mailing lists, and handled all of the correspondence including the reply letters to consumer questions. He established the Penton and Hi-Point amateur racers sponsorship program. His department worked with dealers and race promoters supporting their efforts to promote the dirt bike sport. Anything that was printed for the Penton motorcycle was assembled from Matt’s creative genius. His involvement with motorcycles brought him in contact with John Penton at the right time. His 17 years with Penton Imports and Hi-Point Racing Products were memorable and rewarding.

When did you first get involved with motorcycles?

My interest in motorcycles began when I started reading motorcycle magazines as a youngster. I would walk to the Elyria Harley shop in Elyria, Ohio where I grew up. I really liked the Harley Hummer.

What was your first bike?

My first bike was a 1957 50cc Puch Allstate. That year a new law was passed in Ohio allowing 14 year olds to ride 50cc bikes legally on the street. I saved up $200 from my paper route and bought the Puch new from Sears. It had two speeds and in a crouched position I could get it to go 35 to 38 MPH. After my initial year of owning the Puch, I rode my first enduro on it. I didn’t officially enter the event, I just followed some of the riders for 4-5 miles and enjoyed riding the course. When I turned 16, I sold the Puch to buy a car as transportation to High School.

Tell me more of your background history that led up to your being employed by John Penton.

After I graduated from High School in 1961, I went to the Cooper School of Art in Cleveland, Ohio. It was a two year commercial art school. I lived in Cleveland while attending art school and worked part time in commercial art designing menus, signs, catalogs, layouts, and proofing. After graduating, I worked as the Art Director at an Advertising Agency where I was involved with television and radio ad work. I had met my wife, Barbara Strabele, when we both were attending Cooper School of Art and we began dating.

I got back with motorcycles at the end of 1963 when I bought a used Truimph Tiger Cub for transportation. I liked that bike even though I spent a lot of money and time at Sills Motorcycle shop in Cleveland, buying parts to fix it. It was at this time that I got involved in motorcycle racing. I kept up to date with Ohio race results reading the Columbus Star. My first race was an enduro held in Killbuck, Oh. I rode the Triumph, but only went a mile or two because I had sport tires on it. I bought knobbies for the Cub after that race. It was at this race that I became aware of John Penton, who was also riding. I went to a race in Michigan where I met Russ and Riba Steers who became our good friends. Russ was an enthusiastic Michigan enduro rider who rode a BSA.

In 1965, I rode the 500 mile Jackpine Enduro for the first time on my Triumph. My ride lasted only a few miles from the start in downtown Lansing, Michigan. I decided to listen to Russ, sold the Triumph and bought a new BSA 350cc. It worked well for racing and I rode it in a lot of enduro and scrambles events. As I entered more off-road events, I became better acquainted with the history of John Penton and the story of his racing career.

Barbara and I were married in 1965 and we moved from Cleveland to Elyria, Ohio, my hometown. I had picked up a job there working for American Standard doing their catalog work. Barb had been working for the Bailey Company and the Halle’s Department Store as a fashion illustrator. After our move to Elyria, Barb worked for Higbee’s Department Store doing their window displays.

In 1966 I had quit my job at American Standard and had taken a job with Zarney Advertising in Medina, Ohio. We moved from Elyria to La Grange and discovered that the Sportsman Motorcycle Club had a TT Scrambles track nearby. Barb and I joined their club and it was at one of their events that I officially met John Penton. I first met Al Born at this track when he was racing scrambles. I would submit the club’s race results to the local papers.

When did you start working for John Penton?

In 1967, Barb and I opened our own Advertising Studio in Elyria. We were still involved with the Sportsman Motorcycle Club events and John Penton began to bring his new namesake bike out to the Sportsman track. Through our Studio, I did some of John’s artwork for the new bikes and was writing race results articles in John’s motorcycle paper. By late 1969 John needed repair and parts manuals to get and keep his bikes running. He and I worked out a deal for me to work exclusively for him. I set up a studio and dark room at the Colorado Avenue building in Lorain, Ohio and shut down our Advertising Studio.

What was the most exciting thing that you have done in regards to motorcycle racing?

Before working for John, one of the craziest things that Barb and I did was to promote the first ever Professional MX race that was sanctioned by the AMA. We invested our own money in advertising, press releases, banners and posters. It was held at Dick Klamforth’s track in Delaware, Ohio. Dick Mann and Gunner Linstrom rode in that event along with many Ohio riders. We ran two classes, 250 and open. The event was exciting and attracted a large crowd, but we decided that was the first and last time we would ever do anything like that.

Did you still continue racing while working for John?

I was involved in motorcycle racing almost every weekend, for both recreation and business. We did it as a family. Barb enjoyed the sport and did a lot of pit-crewing for me. Our daughter, Tammy, nearly always went with us to the races, also.

Before joining Penton Imports, I had sold my BSA and purchased a Bultaco. After coming on board with John, I rode, in order, a Husqvarna, a Puch and a 1973 175cc Penton. I quit riding in 1974 after suffering a slipped disc that had me in traction for a month.

What were some of the events that you competed in?

Among the many were the Blackwater, 250 mile Little Burr, 500 mile Jack Pine, Lonesome Pine, Burr Oak National Enduros, Berkshire, most eastern eduros and untold number of scramble events. I never rode in the Six-Days, but did some of the qualifiers.

Did you travel to many of the Six Day events?

Yes, I was at many of them during the Penton era and made movies and photos of the events for John. The first movie I ever shot was the 1972 Berkshire 2-Day National. It turned out good even though it was 45 minutes long. I did the editing, story line and voice over. Barb helped with the sound and work. Three or four copies were made and sent around to Penton dealer open houses and seminars. That movie was expensive to make, but was worth it in the positive PR it created. I do not know what ever happened to the reels for that movie.

In 1973 I filmed the Six Days in Dalton, Mass. with Barb, who contributed the drawings that appeared in the introduction. In 1974, Barb and I were at the Six Days held in Camerino, Italy, where I made a film of the events. I also filmed the 1975 Isle of Mann Six-Days and the 1976 Austrian Six-Days. The 1976 film was never put together. That was just before the end of the Penton Motorcycle era and we knew that it would be a waste of time and money to try to promote it.

When did you wind up leaving Penton Imports?

I left Penton Imports at the end of 1986. I had gotten a Job working for Webb Stiles in Valley City, Ohio. It is a manufacturer of custom engineered conveyor systems and I have been working there ever since. I enjoy my position as Sales and Marketing Manager.

Both you and Barb have been involved with the Penton Owners Group after it was formed. What is it that attracted you to it?

After I left John’s organization at the end of 1986, I had no more contact with motorcycles in the years following, until PaulDanik called to tell me about the newly formed Penton Owners Group. He told me of the group’s aim to preserve the history of the Penton Motorcycle and that appealed to both Barb and me.

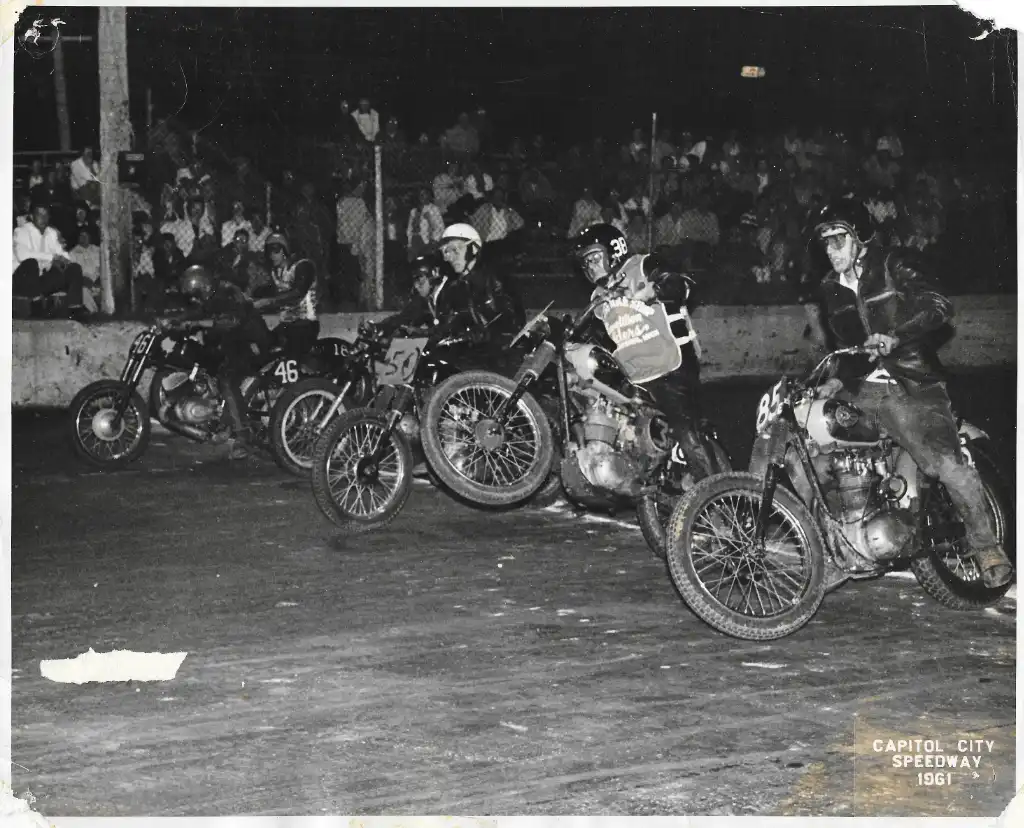

Photos provided by Larry Maiers

My first interest in motorcycles was the result of being in the right place at the right time. I grew up in Lansing Michigan, home of the famed Jack Pine Enduro. And that was a big deal. When the Jack Piners pulled into town, it was a signal for me and the guys I hung around with to ride our bicycles to Oscar Lenz’s Harley-Davidson shop and watch all the riders as they checked in for the start of the race. The day of the race we’d watch them leave town then watch again the next day when they returned. Bench racing was probably bigger then than it is today so naturally we got as close as we could to the riders and listened to their tales of mud holes, deep sandy trails, wide rivers and thick woods. When it was all over we would tape and tie various tools to our bikes, and pretend we were Jack Piners. Needless to say that led to a lot of lost tools and angry fathers.

My first ride on a real motorcycle was with an uncle who had a 650cc Triumph. I think it took just one ride and I was hooked. I bought a used Zundapp and with a little help from the College Bike Shop, my dream of becoming a champion racer was underway.

It didn’t take long for me to figure out that my inability to ride fast would be a career downfall. So instead of becoming a champion, I became just another participant. That was OK because I was not alone.

Of course there were the fast guys who at the time were two-wheeled gods. They collected the trophies while most of us made excuses.

Grand National Champion Bart Markel from near by Flint, gave me advice once. It was at a short track. I think he saw me ride, and felt sorry for me. He said run it into the corner until the rear wheel breaks loose and starts to slide. When that happens, blip the throttle and steer with the rear end. I thought about that for a while, decided it made no sense at all, and if I did what Bart said I was sure I’d hit the track ass-end first. Right then and there I decided enduros and scrambles were more fun than short tracks anyhow, so I tended to stay away from the ovals and the fast guys and their advice.

Back in the late 50's, early 60's, winning was not as important as having fun. And there were a lot of us that rode because of just that. It was fun. The camaraderie was off the chart. Someone would always stop and offer help if your bike quit while out on the trail. Afterwards we’d all get together, drink a beer or two, and tell lies about how fast we were.

If you lived in that era chances are you know what I mean. Getting to the event, hanging out, borrowing, or lending a left- behind part or piece of equipment, a ride through the woods, and afterwards waiting to see who got trophies, was enough. It was the best possible way to spend a Sunday.

I do have one regret regarding not trying harder. I never won a Jack Pine trophy. It seems like I missed every year by just a few points. One year, I think it was 1964, I rode the 500 miler on a Honda Trail 90. I have no idea what possessed me to do it. I guess it was one of those things that seemed like a good idea at the time and it fell into the category of having fun. The fun stopped when I hit the first mud hole. By the time I got there all I could see were bikes watered out or stuck all over the place. As it turned out I was saved by a big floating log. I was able to wheel that little Honda on to the log, then idle it along the log while wading beside it. I passed a lot of riders that were stuck but in the end it didn’t matter As I recall there were only four or five 90cc bikes entered. I rode the entire 500 miles but so did two other guys. They got trophies and I got zip. It was not a total loss however. Vaughn Vandecar, owner of the College Bike Shop was so impressed that I had finished the run, he tore up my parts bill. Since I was always broke that meant a lot, but looking back, I'd rather have had a trophy.

To support my racing habit I worked for Massey Ferguson as a rep in their construction machinery division. My territory included Amherst, Ohio and John Penton's Motorcycle shop. Naturally Penton Honda became a regular stop on my schedule. At that time, it was late 1967, I was riding a Honda SL 90 and had decided to get a bigger bike and mentioned that to John during one of my visits.

John said if I could wait a few months he would have something for me. He explained he was working with a factory in Austria that had agreed to build a few off road bikes to his specifications. Again, I was at the right place at the right time and said “sure I can wait.”

The first Pentons showed up just a few weeks, or days, I don’t remember exactly, but it was just before the 1968 Stone Mountain Enduro in Georgia. Serial number V0002 was mine. When I took it home I was the proudest old kid in my neighborhood.

My first Penton ride was a fiasco. I had coated the air box with grease thinking if any sand got into the box the grease would keep it from the carburetor. Then I reasoned if a little grease was good, a lot of grease was better. No sand made it to the carb, but a lot of the grease did. I barely finished within my hour of grace.

Then it was on to Daytona and the Alligator. If Stone Mountain was a fiasco, The Gator was a total disaster. Somewhere out on the trail John caught and passed me. I decided I was going to give that brand new Penton the kind of ride it deserved and immediately started riding way over my head.

We were on a two track going far faster than I was capable of. Going into a corner we caught a slower rider. John went by him on the inside with me close behind. I tried to shave a couple of feet off the corner and hit either a stump or a ditch that was hidden by the weeds. My brand new Penton came to an abrupt stop while I continued on down the trail at a high rate of speed. From that point the next couple of hours were a bit on the hazy side. I remember a rider stopping to help me. He started my bike, and put me on it. I found a road and made it to the finish line. An operation to remove the cartilage from my knee ended my motorcycle (not so illustrious) racing career. I still rode, but caution was the name of my riding style.

In case you were wondering, the answer is yes. I know where my first Penton, serial number V002 is. Dallas York, former owner of Twin Falls Cycle, took it in on trade and still has it.

A couple of years later I was again at the right place at the right time. John told me his business was growing in several directions and he needed a little help. Would I be interested? A no brainer if I ever heard one. At the time I was living in DesMoines, Iowa with my wife, DiAnn, and two sons, Bret, and recently born Jay. I had a pretty decent job as National Sales Manager of the Massey Ferguson Lawn and Garden Division. I went home and told my wife what I was doing and she said, “You’re doing what?” It was a pretty big leap of faith, but I loved the sport and it was something I was really excited about.

I worked at Penton Imports from 1972 until 1985. If you want the company history and progression during that period of time, you’ll find it in the book “JOHN PENTON AND THE OFF-ROAD MOTORCYCLE REVOLUTION”, written by former AMA President, Ed Youngblood. Not recorded in the book are a lot of behind the scenes stories that affected me as well as the company.

I’ll start by telling you the years I spent at Penton Imports/Hi-Point Racing Products were absolutely the greatest. How could they not be. I was surrounded by motorcycles, the best motorcycle racers in the world, loyal and enthusiastic dirt bike dealers, and extremely dedicated fellow employees. For myself, it was the Golden Years of off road riding.

The AMA was just beginning to establish Motocross National Championships. That led to motorcycle manufactures fielding factory Teams. That in turn led to an explosion in the motocross apparel market fueled by newly hired Pro riders. HiPoint Racing Products was on the ground floor, and initiated some of the first rider sponsorship deals in motocross.

One year, I think it was around 1974 or 75, just to say thank you, I bought some Malcolm Smith wallets and put $500 in each and gave them to a few of the top riders who wore our Hi-Point boots: Bob Hannah, Pierre Karsmakers, Marty Smith, and Brad Lackey. Before long we were giving free boots to the top riders in exchange for advertising rights.

I also made deals with a whole lot of Pro riders that were not turning in advertising type results. I sold them boots at slightly over cost with the understanding that they could resell them when they started to break down. With the money they got for the boots, they then would buy new ones. That guranteed the start line would be full of Hi-Point Boots. I should point out that promotions aside, Hi-Point Boots were absolutely the best on the market.

Bob Hannah was probably the first rider to get big sponsorship bucks from the apparel companies. One of the stories I remember about Hannah was that we had a deal in which Hi-Point paid him in gold for his wins. Hannah would watch the gold market, and when he felt the price was right he would call, and I’d have to quickly come up with the money, and buy him gold Krugerrands.

Sometime in the early 70's John purchased a building that was previously a roller skating arena. This, along with additions added by John became the new home of Penton Imports and Hi-Point Racing. One of the additions was a huge garage that housed the Penton fleet of CycleLiners and semis that were used to haul motorcycles and boots to Texas and California. A side benefit was that whenever the motocross circuit was near our part of the world, the mechanics used that garage to rebuild their bikes between races. It was a great PR tool for us. They wouldn’t do that today, but back then mechanics and riders, regardless of team allegiance, got along with each other and used to caravan from race to race. I use the term caravan loosely. More often than not they raced from venue to venue and frequently waged paint ball wars along the way.

That was part of the Golden Era of Dirt Bikes. We all got along and had a great time doing it. I recall prior to one of the Mid Ohio races John arranged for the Amherst Meadowlarks to open their track to the Pros for testing. To entertain the attendees Hi- Point hosted what we called a Corn Cross. Riders, mechanics, and Ohio's finest corn on the cob, with Jammin Jimmy Weinert on the Guitar. How could it get better than that?

Somewhere along the line, the moped craze bit John and we ended up with a warehouse full of KTM/Sachs Mopeds. What I remember most is the government bumbling the market with legislation that I sometimes felt was aimed directly at putting us out of the moped business. We received a government directive one day stating that fuel shut off valves had to be mounted in a specific direction in relation to the fuel tank. Naturally the valves on our mopeds were mounted just the opposite. I recall saying to John, we more than likely would have to change the valves, but what we should do is go to Washington and find out why. I swear there was glint in John’s eye when he said, “Maiers, thats a damned good idea.”

So we loaded a moped in a van and headed for the home of the Nation's law makers. For two days we went from office to office trying to find someone that could, or would, shed a little light regarding how stupid laws were written. Finally we found the guy that authored the fuel valve directory. He didn’t want to see the moped we had brought from Ohio, nor could he explain the need for the valve to be mounted in a certain direction. He had never ridden a moped, but he did assure us that the directive was based on tests that he was not able to put his finger on right at that time nor did he recall what the tests were. He assured us if we waited around for a few days he could come up with answers. Yeah ----- Right.

We left to go back to Ohio. On the way we had to laugh. I think we both knew when we started out that we were on a trip to nowhere and would accomplish nothing. We succeeded beyond our wildest dreams.

One of my Penton /HiPoint proudest memories came from the results of short-lived Penton Short Tracker. It’s a long involved story but here’s the nickle version.

Carl Cranke was involved with the motor and exhaust. Carl knew 100% what he was doing and what kind of power band was needed. Kenny Roberts told me he had a frame production business. He designed and built the frame. Kenny later admitted he knew nothing about building frames but did know how the finished product was supposed to react when it came time to go left. If it did not react the right way he would simply build another frame making this a little longer, that a little shorter, and increase the angle of the dangle. At least that’s the way he explained it to me many years after the fact. Dirt Tracker Mike Kidd was hired to ride it.

The first outing was the short track national at the Houston Astrodome. During time trials we were holding a Penton dealer meeting. I had asked Mike to come to the meeting and meet the dealers. He said he would try to make it. In the midst of the meeting Mike, dressed in shiny new racing leathers with “PENTON” across the chest, burst into the room. He apologized saying his time trial was not as good as it should have been because he was sick with the flu. He was third. Can you imagine? Against the factory Yamahas, Harleys, Bultacos, Hondas and the rest of the major dollar entries that had been building short trackers for years, Mike was sick and still claimed third fastest time. And he said he was sorry???

Later that night with the race underway, Mike was holding second. He stayed there until near the end when he dropped back to third. On the victory podium I think he said, “not bad for a woods bike.” “If there had been a couple of trees out there we’d have won.” Race results don’t usually bring tears to my eyes but that one did. Unfortunately there was no market for short trackers.

Here’s another story with tears. This one changed the face of American motocross and I’m proud to say I was there all the way and so was Penton Imports in 1981. It started with a discussion between Dick Miller, who was the editor of Dirt Bike Magazine and myself. The topic of the discussion was MotoCross and Trophee Des Nations. Here’s a portion of the story taken from the induction of the 1981 American Team into the AMA Hall of FAME (from their web site):

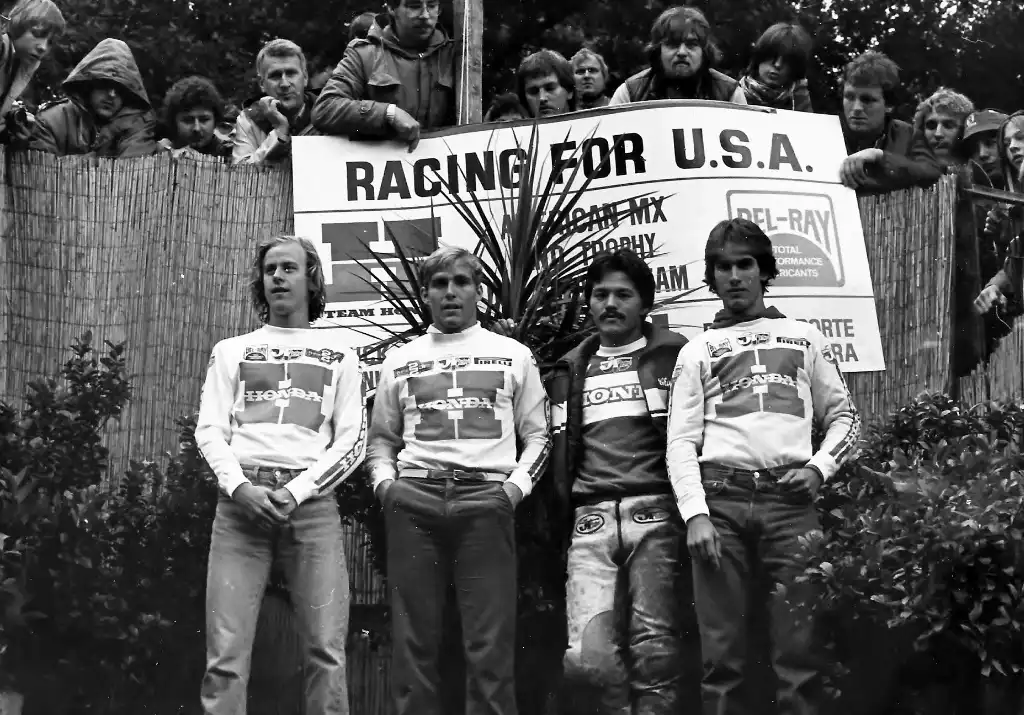

“For a while, it looked like the United States would not send a team to the competitions, but a group of industry enthusiasts, spearheaded by Hi-Point’s Larry Maiers and Motocross Action Magazine’s Dick Miller, convinced Honda to enter its American motocross team in the des Nations. Honda, its sponsor Bel-Ray Lubricants, along with funding raised through T-shirt and product sales and donations, raised the money necessary to field a team.”

“The team’s arrival in Europe was not a warm one. The “no-name” B-team of Honda riders was scoffed at by des Nations officials as being unworthy of participating in the prestigious des Nations competition. Even the riders themselves came only hoping to do well and salvage a bit of respectability for American motocross.”

The no name B team consisted of Johnny O’Mara, Donnie Hansen, Chuck Sun, and Danny LaPorte. The team manager was Roger DeCoster. The B team won the Trophee Des Nations in Lommel Belgium. They won the MotoCross Des Nations in Bielstein, W. Germany. If there were questions in the minds of anyone regarding the state of motocross in America, they were answered in 1981.

Here’s a footnote to the story.

After the event John Penton and I were in the hotel lobby when O’Mara and Hansen came through the door. I introduced John to the pair of MX stars. In the process of expressing his congratulations John touched on his efforts to field a winning ISDT Trophy Team and the number of years he had been at it. As he talked, tears of emotion spilled from his eyes as well as mine. Hansen looked at us and said,

“Mr. Penton, you shoulda sent me and Johnny sooner.”

An area of racing that’s always been a favorite of mine is dirt tracking. I love being in the corner of a mile race track when a herd of Harleys are pitched sideways at about 140mph. Knowing that, you can imagine how many bells went off in my head when the late Ted Boody, a dirt tracker of considerable fame called me and wondered if Hi-Point would let him try some motocross gear at a short track.

Prior to that time dirt trackers wore heavy leather suits and boots from the army surplus store. That was good for the miles and half miles but was not needed for TT’s and short tracks. The use of MX gear as an experiment led to great success. I counted among my personal friends the best dirt trackers in America including the powerful Harley team. It was easy to get them to try our products. All of a sudden MX boots, and gloves started to appear on the half mile and mile dirt tracks. At short tracks and TT’s riders showed up wearing full MX gear. We didn’t sell a lot of product in the dirt track market but we sure got a lot of free advertising.

The ISDT, or International Six Day Trial is something most off-road riders have heard about but will never have the chance to ride. The ISDT is geared toward the best of the best. One that can maintain a grueling pace for 6 days and keep his motorcycle alive and well. I for example would have no business riding the ISDT.

I was however given the opportunity to participate in two events. Camerino Italy in 1974 and the Isle of Mann in 1975. I was privileged to be the manager of the U.S. Trophy team on both occasions. I’m not sure to this day if I managed the team or the team managed me. I am sure of one thing, it was a great honor to be associated with, and to be considered part of a ISDT event.

I was still working at Penton Imports when I began announcing races. Like the other opportunities in my life I was at the right place at the right time. Incidentally that proves what I’ve always known. “It’s good to be good, but it’s better to be lucky.” I was at Red Bud in Michigan when the regular announcer failed to show up. Promoter Gene Ritchie asked me if I would help out. I like to talk and I knew all the riders, so why not. Besides, Gene gave me free hot dogs and all the beer I could drink.

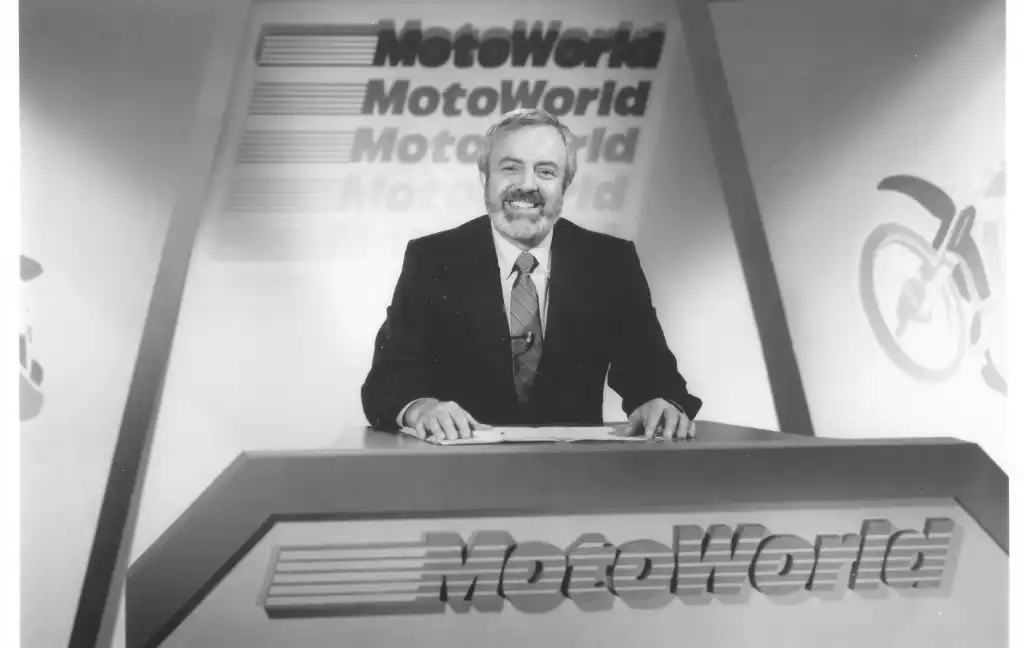

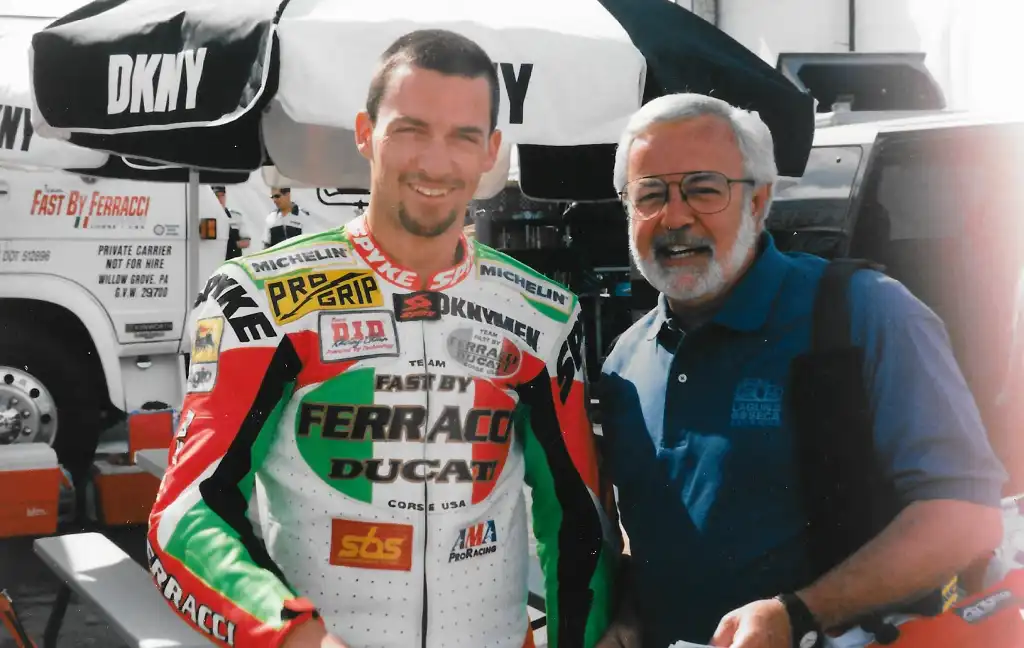

From that first job at Red Bud, all of a sudden I was calling races every weekend. On occasion I traded my services for Hi Point advertising. In those days no one was in line to pour money into motocross, so I’d announce the race and in exchange the promoter called his event the Hi-Point National. Track announcing led to television. Lou Seals approached me and said he was going to put a motorcycle show on television and needed a host. He figured it would be easier to take a motorcyclist and teach him TV, than to take a TV guy and teach him motorcycles. At first I was skeptical and told him yeah sure. Call me when you’re ready to go. I never expected to hear from him again but to my surprise I did. And the rest is history.

MotoWorld made its debut on the USA Network and became the first regularly scheduled motorcycle show on TV. Once a month, I flew from Ohio to Atlanta and spent the day in production. At least that’s how it was supposed to work. Problem was, one day became two. In addition to hosting the show, I ended up writing a good portion of it. I did this with John’s blessing. He thought there was some benefit to be realized from having the president of his company hosting a national television program. I don’t know about that but, I do know it was a lot of fun and it got me closer to the racing fraternity than ever before.

Eventually the show went bi-weekly and then weekly. It was decision time. I had to quit Penton or quit the show. It was a tough decision because I loved what I was doing at Penton Imports. On the other hand it was an easy decision because I was pretty sure the next call would be to replace Johnny Carson. So again I left a stable and established position to begin a new career.

Eventually I left MotoWorld in favor of doing a new show, Bike Week Magazine. Bike Week aired one hour every week on a new network, SPEEDVISION. And while it was a long way from Johnny Carson it did lead to events on live TV.

Here’s my favorite, funniest, and most embarrassing TV story. We were doing a live road race broadcast. Australian Mat Mladin winner of 6 Superbike Championships was on the pole. I had told Mat, shortly after a commercial break we would go into rider introductions beginning with him. This was nothing new since Mat usually had the pole and we had been doing this same thing for the past several races. I was positioned in front of Mat waiting for the countdown from the show's producer. I was talking to my camera man when the countdown began. When the count got to the go point I started my introduction while looking into the camera. I got to the point where I said Mat's name, turned around and stepped sideways out of the shot. I started to ask Mat a question but there was no Mat. While I fumbled for words, I saw Mat out of the corner of my eye exiting a Porta Potty that was about 20 feet away. I had to laugh as I started to apologize to the TV audience. I don’t remember what I said but I did hear loud laughing from the TV truck. Mat? He was smiling all the way from the Potty to the start line. He didn’t apologize to anyone. Just said “I had to go mate”. Obviously his need was greater than ours.

Before I wrap this up, I need to go back to my Penton Imports days and thank my fellow employees. There is no question that John Penton was and still is a man of vision, full steam ahead . We’ll worry about the consequences when we get there. But without the people assembled by John long before I got there, Penton Imports would never have been the trend setter and leader in the “Dirt Bike Off Road Revolution”.

In addition to Penton Imports there were two other branches, Penton West in Sacramento, California and Penton Central in Amarillo, Texas. In house there was an advertising and promotions company, a research and development company, a trucking company, a parts and accessories company, a full blown race team, and a Honda shop. The individuals that worked in and ran those departments of Penton Imports were a family that was not confined to the boundaries of a job description. First and foremost they flat out got the job done. To them I owe heartfelt thanks.

Also, Thanks to the members of the Penton Owners group.

Their dedication to Penton and the sport of motorcycling keeps the memories alive for old guys like me and offers a chance for the younger members to enjoy the legacy. You can’t have life without progress but I’ll tell you this. When it comes to dirt bikes, I’ll take the old days for sure. “Keep your wheels on the ground and your feet on the pegs.”

Story and photos by Will Stoner

I was born December 26, 1949 in Cleveland. I'm a life-long resident of Chagrin Falls, OH.

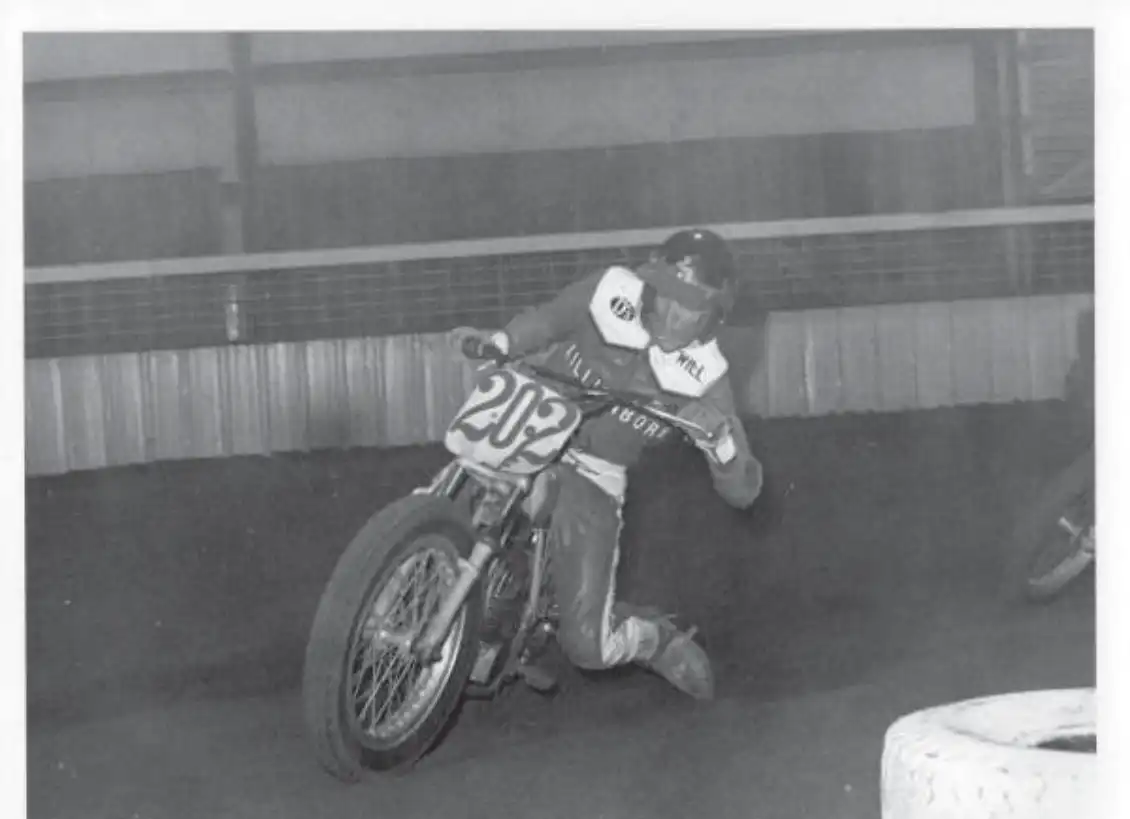

My first love was drag racing, but I married motorcycles. I bought a Honda Scrambler 90 in 1967, which I misused and neglected to maintain for three years. Not only did I not change the oil, I didn't know where the dipstick was. In the summer of 1971, a couple friends got Hodakas and started racing motocross. That sounded like fun, so in November I picked up a very used Hodaka Super Rat for a couple hundred bucks. Indian summer was here on the Thursday I brought the bike home. I rode it in my yard long enough to get huge blisters on both hands. By Sunday the weather had turned to snow for my first race. I slathered around in the mud and managed to complete two laps. That was enough to change my life. By the summer of '72, the drag car lay fallow on its trailer and I was racing motorcycles twice a week.

Track and Motocross license and headed to Springfield, Ohio for the traditional season-opener Pro dirt track race. In the early and mid seventies, dirt track still had more riders than motocross and Springfield marked the end of “Cabin Fever Season” for dirt trackers. Springfield drew riders from all over the country. There were thirty or forty Experts, fifty or so Juniors and ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY Novices. The Novices were divided up into heat races of ten riders each. Only ten riders made it to the Novice Final, so that meant three heat race winners would not make the final.

I was terrified. Novices only got four laps of practice. On my first full-speed lap, I came out of turn two and looked up at turn three. It looked like a solid wall of hay bales. I nailed the brake and hit the compression release. Nine guys flew by me into turn three. I did not finish last in my heat race.

The only forms of motorcycle competition I haven't done are hill climb and enduros. After the Hodaka, I had a brief affair with a ’72 250 CZ. The only good thing that I got from that bike was I met Denny Laidig (a Penton dealer back then and now a KTM dealer). Then came the first in a long line of Husqvarnas, probably fifteen. The Krantz family, George, Peg and racer son Al had a shop in Lakewood, Ohio called Street and Dirt Bike Accessories. Most of my Huskies came from the Krantz’s, but the last few came from Bill and Carolyn Wetzel of Wetzel Suzuki in Mentor, Ohio. I rode Husqvarnas in motocross, hare scrambles and even a few Pro dirt tracks and TTs.

Dirt track racing sunk its teeth into me in 1973. I’d gone to the Charity Newsies in Columbus, Ohio and run local short tracks and scrambles on my MX bikes and most of my bike friends liked flat track. In an argument in a bar in Athens, Ohio my buddy Jeff bet me I couldn’t build him a competitive dirt tracker for his 1974 Novice season. I bought a DT360 Yamaha, Champion frame, wheels, and sprockets and had an engine builder from Michigan breathe on the motor. Jeff won several heat races and came in second in the final at Orville, Ohio in ’74. He came two points short of making his Junior points. Jeff said I won the bet.

Jeff got a full time job in the spring of 1975 and quit racing. After my resounding “success” as a tuner, I figured “How tough can it be to race one of those things?” I got my AMA Pro Dirt Thus began my career as a “Lifetime Novice”. That’s not exactly true, but I’ll get to that later. AMA Pro dirt track racing had a promotion system: Novice, Junior and Expert. All riders had to start as Novices; earn a certain amount of points to become a Junior; then accumulate another set of points to graduate to Expert. Experts were the top of the pyramid. They raced for the Grand National Championship. You needed forty points to move from Novice to Junior. The really fast guys made their points in the first few weeks of the season, even though you couldn’t move up to Junior until the next season. The fast guys made their points in their first year. It took me three. My friend Big Mike dubbed me with the Lifetime Novice title. He also told me one time, “Willie, you’re pretty damn fast out there, but you’re like a rock on the end of a string: You get going faster and faster until the string breaks.” Even though, after three years I did get my Junior points (and Jeff didn’t), I and everyone else consider myself a Lifetime Novice.

Then there were those Pentons. I hated every one of them. When I say “Penton”, I’m not referring to the family. I love them; have since I met them when I worked for the AMA. My racing buddies and I “hated’ anyone who rode a Penton motorcycle in the early Seventies. We hated them because they kicked our asses EVERY WEEKEND! Coincidence made me live smack dab in the middle of all the fastest Penton riders on the planet: Jack, Tom, Jeff, Teddie, Dane, Frank Gallo, the Pieseki’s, Bob Crosier and a host of others. Penton bikes dominated nearly every motocross or hare scramble I entered. Everywhere you’d look, those green (and red and blue and white and orange…) bikes were smoking the competition. If I had really had any animosity toward the Penton family, it would have disappeared when I met them. I’m now honored to consider them friends.

I don’t remember much about racing against the Penton family. I would see them on the starting line, and then I’d see ‘em at the trophy presentation… John Penton, on the other hand, has given me several fond memories off the race course.

By the time I was working for the AMA, I was well aware of JP’S accomplishments, but I had never met or even seen him in person. The only amateur racing class that the AMA requires homologation is the 50cc automatic mini cycle class, the class for the youngest, smallest, least experienced riders. The reason is the Dads cheat like hell.

In January of 1998, Bill Amick, AMA Vice President of Amateur Racing and Special Events, and my boss asked me to go up to KTM Headquarters in Amherst, Ohio to count and inspect the latest batch of KTM “Junior Minis”, their 50cc automatic bikes. It was late on a gray, misty day, not the kind one would like to be outside working. I happened to glance out the window of the warehouse and noticed an older man, in a worn, torn jacket, stocking cap and wrinkled, soiled pants. I thought he might be homeless. Mike Rosso was KTM’s representative with me. I pointed him to the window and asked. “Is that a homeless guy on your property?” Mike said. “Nah, that’s John Penton. He can’t stand to see the place dirty, so he picks up the litter on the property and a half mile along the road in either direction almost every day. That was my first exposure to John’s boundless energy.

The closest to fame I came was winning the 400cc class at the 1979 24 Hours of Nelson Ledges road race in Ohio. But I had three other fast riders and a team of forty people helping. Three months after that race, I suckered one of our crew members, Kit, into marrying me. For the next four years, I dabbled occasionally with bikes until I quit my job and Kit and I started a landscaping company. In an effort to be a "responsible citizen", my stable of motorcycles was sold.

The next two years were spent harassing my lovely bride to let me get another bike. She finally caved in when a friend called the house to ask me if I might be interested his old Yamaha RD250. Several months before, I told the seller, over several beers, to let me know if he ever wanted to sell the bike. I wasn't home and Kit took the call. The selling price was cheap, so she decided to surprise me and have Teddy, the seller, bring the bike to our house that Sunday, knowing that I wouldn't be home until late afternoon. Whatever I was doing turned out to be a bust, so I went home early. You'd think I'd caught her in the bedroom with a boyfriend. She was red-faced and fidgeting. Then Teddy pulled into the driveway with the Yamaha. We walked out to the drive to greet Teddy. I'm so stupid. I said.

"I know Teddy wants to sell this bike. Can I please buy it?”

Smiling, she said "No."

"Why not?"

"It's sold". She said, grinning more. Did I mention I was stupid?

"Who bought it?"

"A woman." She said with a bigger grin.

"Did Grace (a former owner of the Yamaha) buy it?”

"No…." she giggled. The light bulb goes on. I start crying. She starts crying. We start hugging and kissing in the driveway. Teddy thinks we're nuts. Two weeks later I have a trials bike. I'm back in the motorcycle game.

I start riding trials, where I meet Bud Kubena and his then twelve-year-old son, Kerry. Bud is a BSA enthusiast and he and Kerry restore old British bikes. I tell him I'd like to get an old Triumph to restore. He tells me about a 1968 Bonneville rolling basket-case in Pennsylvania. I buy it. The disease sets in. It's incurable.

In the fall of 1989, we're at a friend's party and I'm, of course, talking bikes with another friend, Bruce. We're talking about BSA Gold Stars and Bruce mentions that he has a 1956 BSA B33, the Gold Star's Conservative sibling, which he wanted to sell. I go over to Bruce's house. The bike is really neat. I want it. Bruce is asking $1,100 for it. I don't have $1,100. He says it's mine whenever I want it.

I get a Genius Idea! I'll put on a swap meet. I'm an expert at swap meets. I've been to three. I rent the Chagrin Falls National Guard Armory in Ohio for a Sunday in February, 1990. I scour the phone books, bike mags, and harass friends for addresses. I send out thousands of post cards. I make tons of phone calls. I sell out the Armory: all forty-five spaces! I'm excited. This is great.

It snows eighteen inches Saturday night before the swap meet. I have a landscape business. We have over one hundred plow customers! My seventy five year old mother gets stuck in the snow. I have to go rescue her in the blizzard. I'm having a heart attack!

The snow stops. We get the plowing done. It's 6:00 AM and I drive by the Armory. There are tracks leading in. I figure it's the Sergeant and he's clearing the parking lot. I drive in and there's a guy in a red pickup truck, waiting to get into the meet. I have to plow the parking lot.

Time comes for the show. We pack the place. Everybody has a great time. I make enough money to get the bike. I call Bruce. He says "Ya know, I've decided to keep the bike." I'm now in the swap meet business! Note: Bruce sold the bike to someone else a few years ago. If he weren’t such a good friend, I’d still be ticked at him.

We always invited the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) to set up a membership table at our swap meets and I became friends with Field Rep Jim Nickerson. I fool him into thinking that I knew what I was doing, so when Mark Mederski, then AMA Vice President, asked Nickerson if he knew anyone who could put on a swap meet, Jim suggested me. Mederski was as easy to buffalo as Nickerson; I produced the swap meet and assisted on other elements of the event at the first AMA Vintage Motorcycle Days (VMD) in July, 1992.The AMA kept me on as an outside contractor to produce the swap meets at VMD through 1997. In 1998, I became full-time employee of the AMA, their Special Events Director. In addition to being responsible for all aspects of VMD, from Grand Marshals to Porta-Johns, I helped produce several AMA International Women & Motorcycling Conferences, Hall of Fame Inductions, as well as producing four AMA Swap Meets each winter. It was my “Dream Job”. I said “I got paid to do what I’d do for free”.

I started planning for the 1991 swap meet in July by reserving National Guard Armory for the middle of February. Unfortunately, I forgot to check with George H. W. Bush. He decided to have a little party in Kuwait. All the Armories in the country were closed to the public in December, 1990. We were out of a site for our event with about two months to find a new site and change all our advertising. In the event promotion biz, two months is like fifteen seconds. The weekend after I got the news that the Armory was unavailable, a couple friends of mine and I decided to drive down to Westerville, Ohio to see the latest exhibit at the AMA’s Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum. On the way down on Interstate 71, I noticed a building called the “Burbank Auction Barn”. It looked big enough to hold a swap meet. I scribbled down the phone number, called the guy Monday, went down to inspect on Tuesday and signed the contract on the spot.

Burbank is where I met Mark Mederski, starting my journey with the AMA. It’s also where our swap meet business took off. We’d sell out the fifty-some indoor spaces, but more vendors would show up the day of the show. Not wanting to leave money on the table or disappoint my fellow motorcycle enthusiasts, I charged half price for the outdoor spots. We filled the outdoor spots at every event in Burbank, no matter the weather.

After three years at Burbank, the owner announced he was selling the building. We had already outgrown the place, so we started looking for a new venue. I was looking at fairground facilities, found the Richland County Fairgrounds in Mansfield and moved our events there in 1993. The building held nearly a hundred vendors and had a huge, paved parking area. The big parking lot was a good thing, because the outdoor vendors followed us to Mansfield and brought their friends. Several times we had ninety vendors inside and forty or so outside. We continued with two meets a year at Mansfield until 2003 when the AMA, decided to discontinue our winter swap meets. We also produced swap meets in York, Pennsylvania from 1992 until 2002. I picked York because my brother lives there. I saw their beautiful facilities on a trip to his house. York brings back the memory of the strangest happenings ever at one of our events. One of our regular vendors at York was an Englishwoman named Marie, who sold Rocker-style pins and badges. She apparently had some “outlaw biker” pins for sale too. That did not sit well with a bunch of thugs who call themselves the Pagans. Marie had been warned at a previous event not to sell “1%” pins. She also turned out to be the ex-girlfriend of a member of the Hell’s Angels. Angels and Pagans don’t exchange Christmas cards. By this time, the York event had enough vendors to fill two buildings. While I was in the other building, several Pagans had come up to Marie’s booth, knocked over her tables, roughed her up and scattered. Even at a motorcycle swap meet, outlaw bikers, with their unwashed regalia, stick out like tank tops and flip-flops on Prom night. I walked up to the first one I spotted. With my luck, he was about six-foot-six and chiseled from granite. I asked him to take his friends and leave before I called the police. After his expletive filled response, I walked away, pretending not to be terrified. As I was going back to the first building, dialing the police on my cell phone, the big one came up behind me, knocked the phone out of my hand and I skittered down the alley like a scared bunny. A couple weeks later my brother, who had witnessed the festivities, told me that his local TV news reported that the Pagans and Angels had a shoot-out in Allentown. The newscast showed pictures of the deceased combatants. Brother John was sure one of them was the guy who threatened me. Paybacks.

My last event with the AMA was the 2008 Vintage Motorcycle Days. The event set the record for the biggest attendance, most vendor spaces sold and the largest profit for the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. I went on to produce several more events on my own in Ashland and Medina, Ohio, York, Pennsylvania and Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin.

In 2012, I announced that I was retiring from the swap meet business so I could spend more time working on and riding my own bikes. It didn’t take. I’m doing three events a year at the Medina County Fairgrounds for the great folks at Lowbrow Customs. Additionally, I have just come to an agreement with New Jersey Motorsports Park (NJMP) to produce the swap meet and club corral elements of the July 11-13, 2014 NJMP Vintage Motorcycle Festival. Somehow I’ll still squeeze in some riding and wrenchin’.

Next to my wife, Kit and my children, Kit and Scott and Annie, the greatest treasures I possess are the wonderful friends throughout the world I have made from motorcycling.

My motorcycling adventures started with my brother wanting a Honda to ride to school. It was 1965, and my dad traded a local Honda dealer some landscape work for a Honda 150 Dream. It didn’t take too long for my brother to run the Honda off the road into a ditch, even though he wasn’t hurt, I don’t think he ever rode the bike again. I had been mowing lawns and had bought a nice stereo system. My brother was about to leave for college so I traded him my stereo for the Honda. I don’t know the exact ratio of hours working on the Honda verses riding it, but my tools got a lot more of a workout than my helmet.

I loved to ride the Honda around our nursery. I would race up and down each row of trees and try to make the turns as tight and fast as possible. I slowly ventured further from home to ride some of the farm roads in the area. My mom mentioned one evening that she heard that a semi-retired motorcycle racer had moved just up the road. I decided to take a walk over and see what I could find out; this was one of the best moves of my life. As I approached the couple who were doing some yardwork, I asked if he was a motorcycle racer. “Who the hell wants to know?” he asked. His wife scolded him, saying that he might scare the kid away, fat chance!!! That was my introduction to Bob “Augie” Augustine and his wife Sandie. After that I seemed to live at Augie’s as much as I did at home. Augie had done quite a bit of racing in his day and sure was a lot of help to a 14 year old kid trying to ride a 150 Honda Dream in the woods.

Sandie worked at Fran Kupec’s Honda shop and they became a very early Penton dealer. Augie mentioned to me about the Penton motorcycle and said that if I wanted to ride the local mud runs and ride in the woods, that would be the bike to get. My dad somehow came up with the money and I became the proud owner of a very early Penton. It had the 4 bolt drive unit for the sprocket and the early cast airbox. I think the serial number was around 149. I later took the airbox off and replaced it with a filtron sock style air cleaner. I hung the airbox on a nail in the nursery shop and it stayed there for 30 years until Norm Miller needed an airbox for his restoration of Penton #001. I gave Norm that airbox and I am proud to have helped him with his project. As you can imagine, it didn’t take a now 15 year old kid too long to have a few shifting problems with his Penton, mostly from power shifting second and doing wheelies up the nursery lane, even after dark with the floodlights on!!

Sachs engines were and still are quite a bit different than Hondas, so the mechanics at Kupec’s were not able to solve my shifting problems. Sandie called Penton’s and explained the problem. They said to bring the bike over and they would look at it. Since I was still too young to drive, we loaded the bike in Augie’s pickup and Sandie drove. This would be the first of many trips to Amherst, Ohio. Mr. Penton himself did my transmission repairs and showed me what he was doing. He finished up the job and turned to me, “there” he said, “Now I want you to go back to Pennsylvania and help keep these Pentons running.” I think I know how Noah felt when the Lord asked him to build the ark! After we left the shop, we went over to the Penton Farm Market. A shipment of bikes had just arrived and were to be stored above the market in the upstairs of the barn. My job was inserting the owner’s manual and assorted literature that went with each new bike through the grab hole in the crate. I also met Jack Penton on that trip. He and I sat together on some cases of oil while awaiting his dad. Jack showed me pictures of his big brother Jeff in a motorcycle magazine winning some big race. I was awestruck that this guy’s brother had his picture in a real motorcycle magazine. Almost 30 years later, Jack and I, along with several other gentlemen, sat within 5 feet of that very spot and worked on forming the Penton Owners Group.

I rode lots of mud runs, motocross and even some observed trials with my Penton. As time went on, I was able to place in my class and even racked up a few wins. With guys like Jake Fischer, Ron Bohn and the Lojack’s at all of our local events, we didn’t lack for competition. I always tried to find out where the Penton “boys” were going to be racing and tried to run against them as much as possible. There was always a special electric in the air at a race when they were there. They were the “top guns” of the races, but they were also very easy to talk to and were always willing to help a fellow Penton rider. I remember the State Championship MX race at State College, Pennsylvania. Jack and Tom Penton were there. I was able to beat Tom, but Jack won the event. Afterward, Jack and Tom came over to our truck to sit and talk. Sandie and Augie’s daughter Robin had made the trip with me and reported to her dad that things were improving. The Penton boys came over to our truck after the race instead of the other way around.

I raced a double header MX at Bel Mesa Raceway in West Virginia. I always liked that track. A kid on a 125 Suzuki was tearing up the place in practice, so I watched for him to go back out and ran some practice with him. We ran pretty hard in each of the six motos, but it was my day. I won five of them and he won the other. Afterward, a big man walked up to me and asked if I was the kid on the Penton. I said I was, he said he wanted his son to meet the guy who had beaten him. His son was on the Suzuki. We shook hands and talked for a bit. Years later, Joe Barker was staying at my house as we trained for the 1973 ISDT and as we traded war stories, it turned out he was the Suzuki rider at Bel Mesa that day. Another crazy thing happened that day. Two older riders from the Pittsburgh area came over to me and said that if I was to slow down a bit, I might make a decent enduro rider. I asked them about this enduro stuff and one thing led to another. I went with them the next weekend and rode the Little Hocking Enduro and won the C class overall, and I was hooked. Every weekend I was off to either New York or southern Ohio for an enduro. I won highpoint “B” at the Newark, New York national in my 9th enduro and received a bit of praise in the Penton newsletter. Most enduros were about 5 hours from home and many a Monday morning I had only gotten a few hours sleep before my dad would holler for me to get up as we had a landscape job to do.