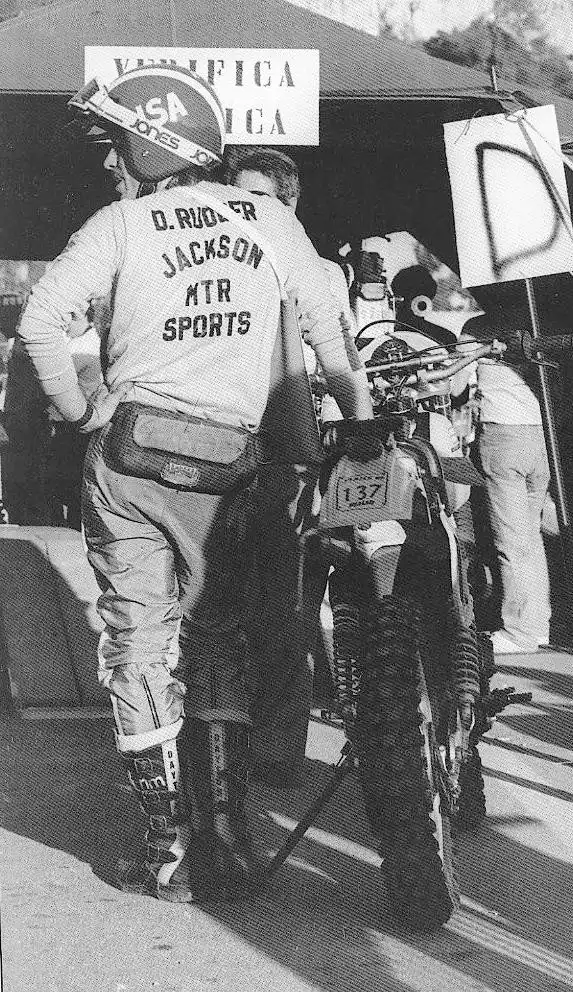

Dwight Rudder

BEEN THERE, DONE THAT

by Ted Guthrie

Originally printed in the 2009 issue #43of Still….Keeping Track

Alabama native Dwight Rudder is “the real deal”. He’s been on numerous factory enduro teams, earned medals in multiple ISDT competitions, has been an “A” enduro rider for decades, and those are just a few of his motorcycling accomplishments. There is in fact a lot more to this quiet, polite fellow with the southern drawl, besides.

Dwight was raised in Greensboro, Alabama, hence the southern accent. However, where his exceptional motorcycle riding skills came from is anyone’s guess. He didn’t come from a motorcycling family, but Dwight’s father did introduce him to the sport at age 9 with the gift of a lawnmower engine-powered minibike. Dad also had a Harley 165 stashed in the barn, which was brought out and coaxed back into operation when Dwight was 12. While Dwight did put some time on the bike, he was initially scared of it. Later came another minibike, but then Dwight graduated to a Suzuki T250 Scrambler. Despite its rough and ready moniker, the Suzuki didn’t turn out to be a very good trail bike. As a result, Dwight traded it for a ’69 Yamaha AT1, aboard which he rode his first enduro in 1971 in Brent, Alabama and his second a few weeks later at the famous “GOBBLER GETTER ENDURO” in Maplesville, Alabama.

Along about this same time, Dwight’s father took him to see the motorcycling film classic, “On Any Sunday”. Although Dwight enjoyed the entire film immensely, it was the segment which featured Malcolm Smith’s performance in the International Six-Day Trial that really excited the young racer. Right then and there Dwight decided that ISDTtype competition was going to be his primary pursuit and Malcolm Smith became his number one hero. So, how did a young man correspond with his hero back in the 1970’s? Why write fan letters, of course. And, being the friendly guy that he is, Malcolm responded with letters of his own, as well as photographs of himself and his motorcycles.

Meanwhile, Dwight had moved on to a Yamaha CT-2 175, followed by a 175 Jackpiner, and then a Penton 125 Six-Day, on which he began competing in 2-Day Qualifiers. At the Ft. Hood, Texas Qualifier, in 1975, Dwight had stopped alongside the trail to fix a problem with his Penton’s throttle cable when none other than Malcolm Smith himself stopped to see if he needed any assistance. Dwight already had the cable repaired, but he did however accept Malcolm’s offer for them to ride together. And so it was it was that Dwight found himself riding in the company of his boyhood hero.

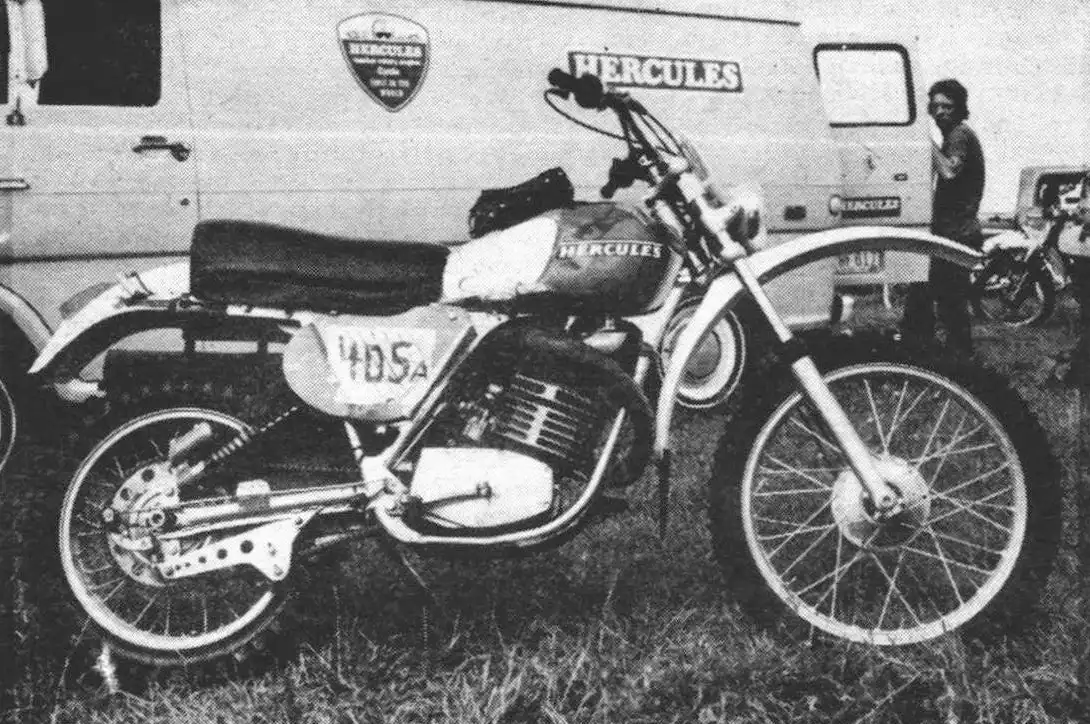

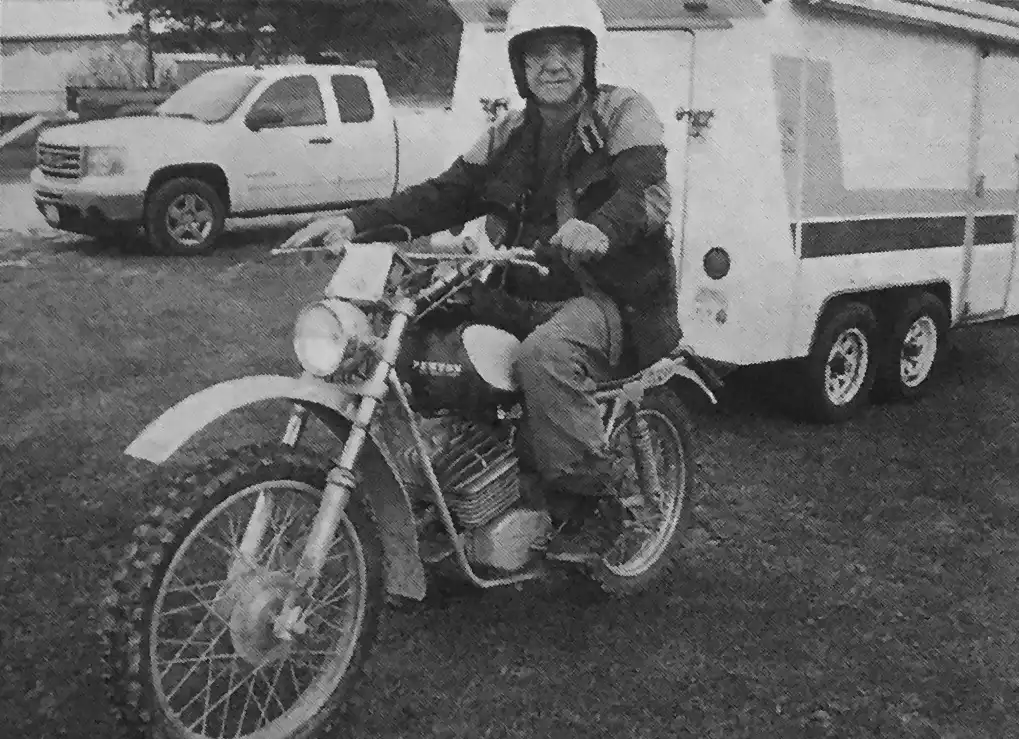

This very special experience came to a premature end though, when Dwight’s 125 Six-Day sheared its shift key. By the time Dwight managed to get in off the course, it was late and nearly everyone else was packed up and gone. Among those still around however was Malcolm, who promptly came over to talk to Dwight. Malcolm complimented the young Penton rider on his fine ride earlier in the day and when Dwight introduced himself, Malcolm’s eyes went wide and he took a step back. “There used to be a kid by that name that wrote fan letters to me!”, he said, partly surprised and more than a little impressed as Dwight turned a very embarrassed red. Dwight recalls that he will never forget this initial meeting with Malcolm Smith. The entire experience, from riding with his hero, to Malcolm actually remembering him from the fan letters, absolutely galvanized Dwight’s opinion of Malcolm Smith as a top rider and as a wonderful person and they remain friends to this day. Dwight Rudder rode this prototype 125cc

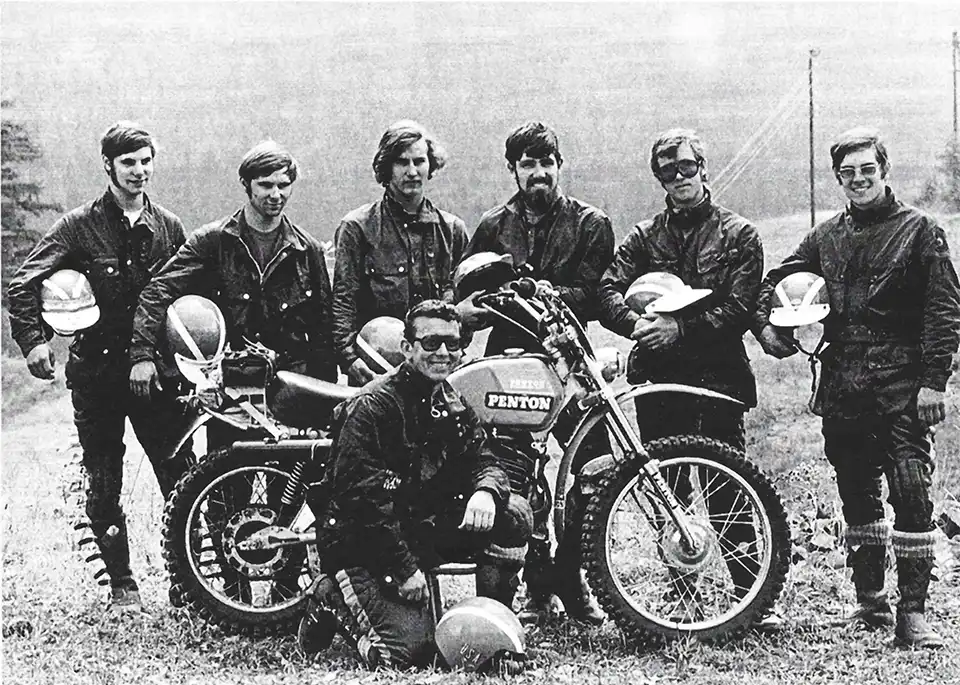

Dwight continued competing in the Qualifiers, and did quite well. He met the Penton family and the entire Penton team, and was very honored when Dane Leimbach invited him to pit out of the famed Penton Cycleliner. Then, during the offseason, just after moving from Alabama to a new home in Jackson, Mississippi, Dwight was contacted by Doug Wilford, with an offer to ride Hercules motorcycles the following year. Doug had at that time recently taken a position with the Hercules importer and recognized the talent and potential of this young rider.

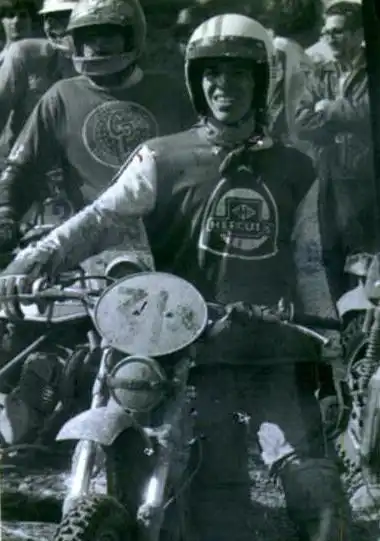

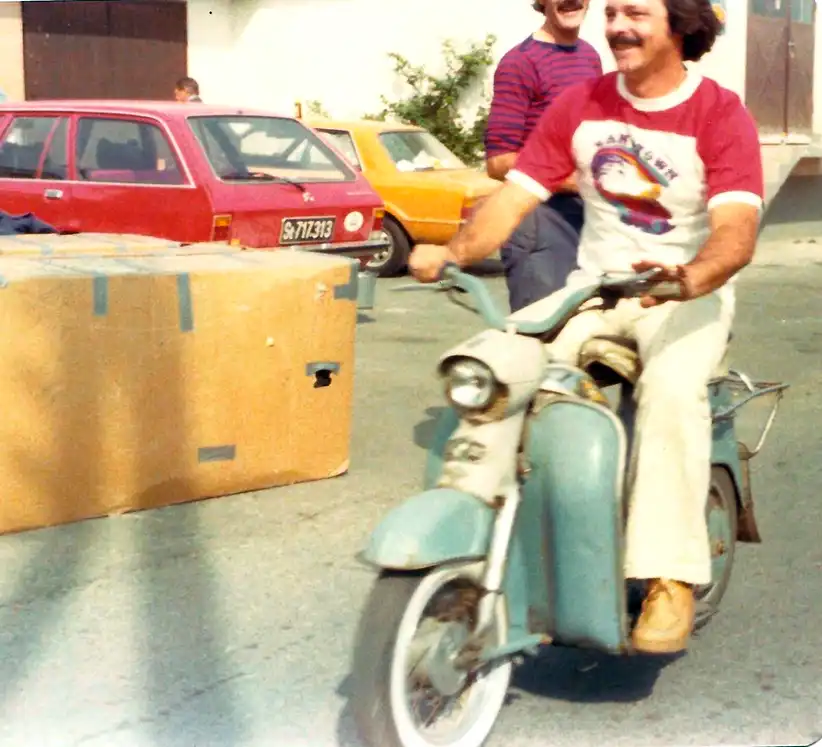

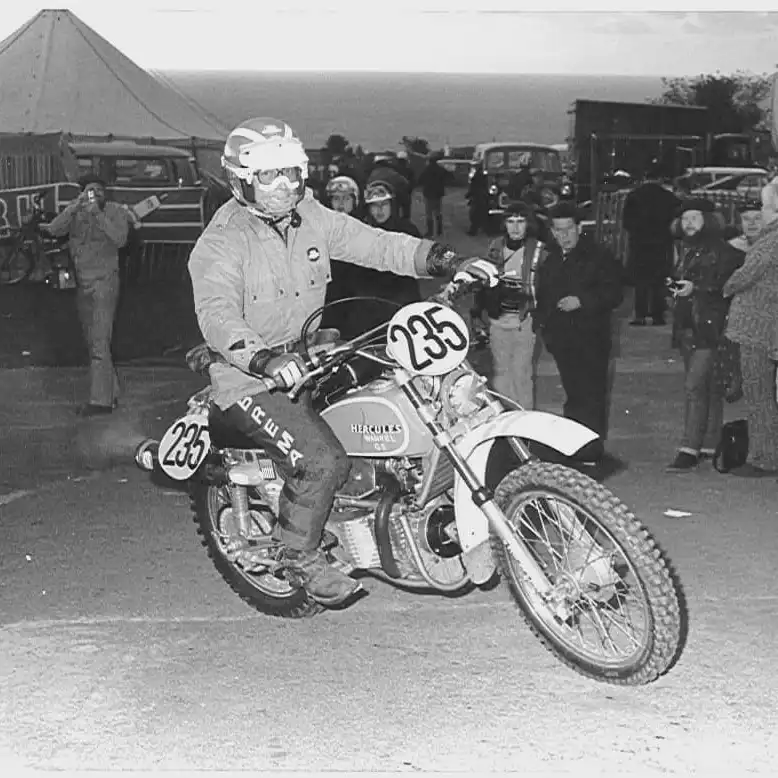

The first time Dwight had any experience at all with the Hercules motorcycles was early September, 1975, when he met with Doug at Tennessee’s Loco Ciento 1-Day Qualifier. There, he rode a prototype 7-speed Hercules 125. Despite drowning the bike out in a creek crossing due to what Dwight determined later to be poorly placed louvers in the airbox opening, Dwight tied for 2nd place in the 125 class with his friend, Teddy Leimbach. Steadily gaining experience through this and other strong rides aboard both six and seven-speed Hercules 125 and 175 models, Dwight remained with the team from 1975 through 1977.

Dwight’s performances during this time qualified him to ride the ISDT in ’76. Unfortunately, he was denied the opportunity by Al Eames, who told Dwight that he didn’t have enough experience. “Rider selection for the ISDT team was not an entirely Democratic process back then”, Dwight comments dryly. Dwight also qualified to ride the ISDT in 1977, but was injured prior to the event. This particular injury was not the result of either a motorcycle riding or racing accident, but rather from another aspect of Dwight’s amazing life experiences.

This goes back to Dwight’s father, who was in the Air Force. Although Mr. Rudder did not serve in the USAF as a pilot, he did earn his pilot’s license while in the service. He then started his own crop dusting service in Alabama and later in Mississippi. Exposed to his father’s experience and influence, Dwight earned his student pilot’s license at age 14, followed by a commercial pilot’s license as soon as it was legal to take the test. And so, it was in one of his father’s crop dusting planes that Dwight suffered injuries which prevented him from participating in the 1977 ISDT. While flying over a particular farm field in Canton, Mississippi, while crop dusting, Dwight saw that the aircraft was going to come too close to some power lines. He managed to avoid the power lines by flying under them, but then could not quite clear the trees on the other side. A large tree ripped one of the plane’s wings entirely off, causing the aircraft to spin three times before crashing into the ground. Dwight suffered a broken collarbone, as well as a concussion so severe that it left him blind for several days. This unfortunate situation did result in one positive however, as it was during his recovery time that Dwight began to date a young lady named Debbie whom he had met some time before. The courtship blossomed and Dwight and Debbie eventually married, the union having lasted now for more than 30 years.

The year after his accident, Dwight was selected to ride on the brand-new Yamaha factory enduro team, along with Dane Leimbach, Carl Cranke, Chris Carter, and Jim Fishback. And, Dwight once again qualified well enough to ride the ISDT. Once again however, he was denied the chance to ride the event, this time by “team politics”, as Dwight puts it. The AMA wanted a SWM rider on the team and told Dwight that they had enough Yamaha riders. (That SWM rider went out on Day 2).

The Yamaha ride lasted only through the 1978 season, as the team was dissolved after just one year. However, Dwight did pick up partial support from Suzuki for 1979, and aboard the yellow bikes rode his first ISDT, held that year in Germany where Dwight earned a silver medal. Riding for Suzuki again in 1980, Dwight missed out on that year’s ISDT due to a dislocated ankle suffered at the Trask Mountain Qualifier.

In 1981, Dwight was convinced by Suzuki to assist in creating and campaigning a one-off concept enduro bike. The machine was based on an RM125 motocrosser, but was fitted with different gearing, altered power characteristics, modified suspension, a lighting coil, enduro lighting, and a larger fuel tank. This motorcycle became the world’s only factory PE125. Dwight qualified on the bike for the ISDT, which was held that year on the Island of Elba, located in the Mediterranean Sea. The Suzuki performed well, and Dwight was well on his way to earning his first gold medal when the bike’s pipe cracked during the final moto. The resulting devastating loss of power dropped Dwight in the field, resulting in a silver medal finish. Surely an outstanding performance regardless, but sadly just short of Dwight’s ultimate goal.

In 1982 Dwight signed on for a support ride with Husqvarna to campaign a 125XC. He qualified once again for the ISDT, held that year in Czechoslovakia, an event which would become known as one of the toughest ever in the history of the Six-Day Trial. In terrible conditions rain, cold, mud, and more rain, over some of the toughest terrain imaginable, all the riders in the event struggled.

Dwight performed well on the little 125 Husky until the third day when he blew out his knee. He continued to ride however, in tremendous pain, and unable to even stand on his right leg. Also, through a combination of the wet and cold conditions, Dwight suffered hypothermia. And yet, through shear determination and by carefully limiting use of his injured knee, Dwight managed to finish the event - one of only 8 Americans to finish, out of 36 that started. He credits part of this accomplishment to, of all sources, riders from the Czech team with whom he had made friends. These competitors, who had dropped out of the event due to mechanical problems, would go out to the really impossible sections of trail and wait for Dwight to come along, then help him through. Such outside assistance was not entirely illegal in this particular ISDT, as even event Course Marshals were involved in assisting riders through certain impassable areas. The conditions were that tough.

For the 1983 season, Dwight decided to switch to competing in the U.S. National Enduro series. He started out riding a private Maico Enduro, but soon decided the bike was not well suited for enduro competition. He then switched to a 250XC Husky, and promptly won the A-class overall in his first National Enduro (Little Harpeth Nat’l Enduro). Dwight went on to finish the season first 250A, Overall A, and 5th overall for the year, then moved up to the AA class. In 1985 he rode a 350 KTM, then in 1986 was selected to ride for Kawasaki’s Team Green, on a KDX200. Dwight enjoyed a number of good rides aboard the KDX that year, including a third place overall in the Jack Pine Enduro.

In 1987, Al Baker offered Dwight a ride on XR250 Hondas. Together with Al, Dwight modified the bikes, increasing displacement to 280cc, along with numerous other modifications and improvements. On one of these XR’s, Dwight rode the ISDT that year in Poland, competing in the 350 class. Riding on Gold time, Dwight crashed hard on the last day. He got up and continued on, but at the next checkpoint noticed oil leaking badly from the bike. An inspection showed that the crash had apparently knocked a hole in one of the sidecases. Working frantically, Dwight was able to clean the case well enough to get some epoxy to at least stem the oil loss. Armed with a couple of extra bottles of oil, Dwight took off down the trail. He had lost much time however, and saw his gold medal slip to a bronze by the finish.

Determined to wring even more power from the XR250 motor for the next year, Dwight punched it out to 300cc and installed a custom built Poweroll stroker crank. Despite Al Baker’s concerns that the motor would never last, Dwight began competing on the bike and found it to be reliable as well as a virtual rocket. Unfortunately, on the eve of that year’s ISDT while putting the bike through final tuning, the engine did blow up. In desperation, and with no time to spare, Dwight and Al took the motor from Al’s personal XR and installed it in Dwight’s bike. While not on par with the power Dwight had built into his own motor, the one from Al’s bike would have to do. Only one problem – Dwight noticed that there were no serial numbers on the cases. Al explained that through all the development work he had done on the motor, the cases were “replacement” parts and so had no factory serial stampings. With nothing to lose, Al produced a set of metal engraving stamps and he and Dwight proceeded to mark the cases with the ID: “OICU812”. And, with this fictional serial number the bike passed tech inspection and Dwight rode it successfully in that year’s ISDT.

For the 1989 season, Dwight duplicated his ’88 XR300, but this time supplemented with a higherperformance cam, supplied by Mega- Cycle. The stroker crank was once again employed as well. Dwight had determined that the ’88 failure was the result of a mechanic failing to re-weld the crank properly, and so felt confident of the reliability of this setup. Besides, the bike was now even more of a rocketship. Dwight reports that the power he got out of the little four-stroke engine was just amazing. And, the bike’s overall performance was vilified by Dwight’s successful ride to a Gold in the German ISDT that year.

For 1990, Dwight went back to Suzuki for a season, riding a DR350. Aboard it, he won the 4 stroke A class in National Enduro competition. Then, for the next few years he returned to riding Honda XR’s – but this time on the booming 600’s. For several years he continued to ride the big Honda four-strokes, regularly winning his class in national competition. Dwight’s final ISDT appearance was in 1994, when he competed once again on a modified XR250 (315cc) Honda, and earned a silver medal. In his 7 ISDT and ISDE competitions, Dwight earned 1 gold, 4 silvers, and 2 bronze medals, finishing every event.

So, with all these experiences under his belt, what is Dwight Rudder up to these days? Well, he still competes occasionally in National Enduros, and consistently places well in the Super Senior Class. He also rides the Senior A class in Southern Enduro Riders Association events. He also collects vintage motorcycles, which presently number “about 70” according to Dwight. Note that all of these bikes are “riders”, and almost all are vintage enduro bikes. Dwight has a couple of older street bikes, including a 1989 Honda GB500 single – well known among collectors for its classic British club-racer styling. And of course several Pentons are part of Dwight’s collection, including at present a Steel-Tanker Bershire, a Steel-Tanker Six-Day, a CMF Six- Day, and a ’73 Jackpiner. His preference in regard to collecting and maintaining his bikes is originality, Dwight reports. He likes the bikes to maintain their original appearance and performance. There are a few exceptions of course, such as his slightly modified 1987 Honda XR200R that he rides in Post- Vintage and modern events, as well as a somewhat “breathed-on”, modern, aircooled, Honda CR230F that he is currently racing in the modern Enduros and in Hare Scrambles. Dwight is also a history buff, participating in Civil War reenactments. And, he maintains his pilot’s license and love of flying as well, having recently owned and flown a replica of a 1916 WWI French Nieuport aircraft.

Dwight has worked for the wholesale motorcycle parts distributor, Parts Unlimited since 1987. Wife Debbie is involved with the motorcycling sport as well, having pitted back in the old days not only for Dwight, but for the Yamaha and later the Suzuki and Husqvarna Enduro Teams. Today, Debbie continues a role she has held for some years as the Secretary/Treasurer of the Southern Enduro Riders Association. “She knows her stuff, too” Dwight says. “Why, over the years many top riders such as Dick Burleson have approached her to ask questions in regard to the association’s rules and regulations.” Debbie tried her hand at enduro competition, but these days is content primarily to zip around to gas stops on her street-licensed Yamaha TTR125.

When asked about stories from the old days, Dwight says that he hardly knows where to start. Some of the stories involve riding and racing of course, but there are also “behind the scenes” recollections. One such story is from the ’82 ISDT in Czechoslovakia. Dwight described how the British team, in a fit of overzealous revelry, hoisted a GORI motorcycle up on top of the entrance awning of the hotel where the English-speaking riders were staying. Responding to the disturbance from this activity, the local police arrived and burst into the hotel room, through which the bike could be accessed. By coincidence, said room was occupied by Jack Penton, who had no idea what was going on and was more than a little concerned about a group of Czech Republic Police storming into his room. However, they merely wanted to haul the little motorcycle through Jack’s window in order to return it to street level and to its rightful owner.

Like all of us, Dwight is feeling some aches and pains these days and injuries from over the years have begun to catch up with him. He has the bad knee, issues with the rotator cuffs in his shoulders, and has had surgery on his back as well as some work done to repair a nerve in his neck. However, you wouldn’t know it by the way the man still rides. And so, look for Dwight at this year’s ISDT Reunion Ride. You’ll never know what bike he may turn out on, but just look for one of the really fast guys, sporting an American ISDT helmet, and who talks with an unmistakable southern twang.

by Ed Youngblood

Originally printed in the 2006 issue #33 of Still….Keeping Track

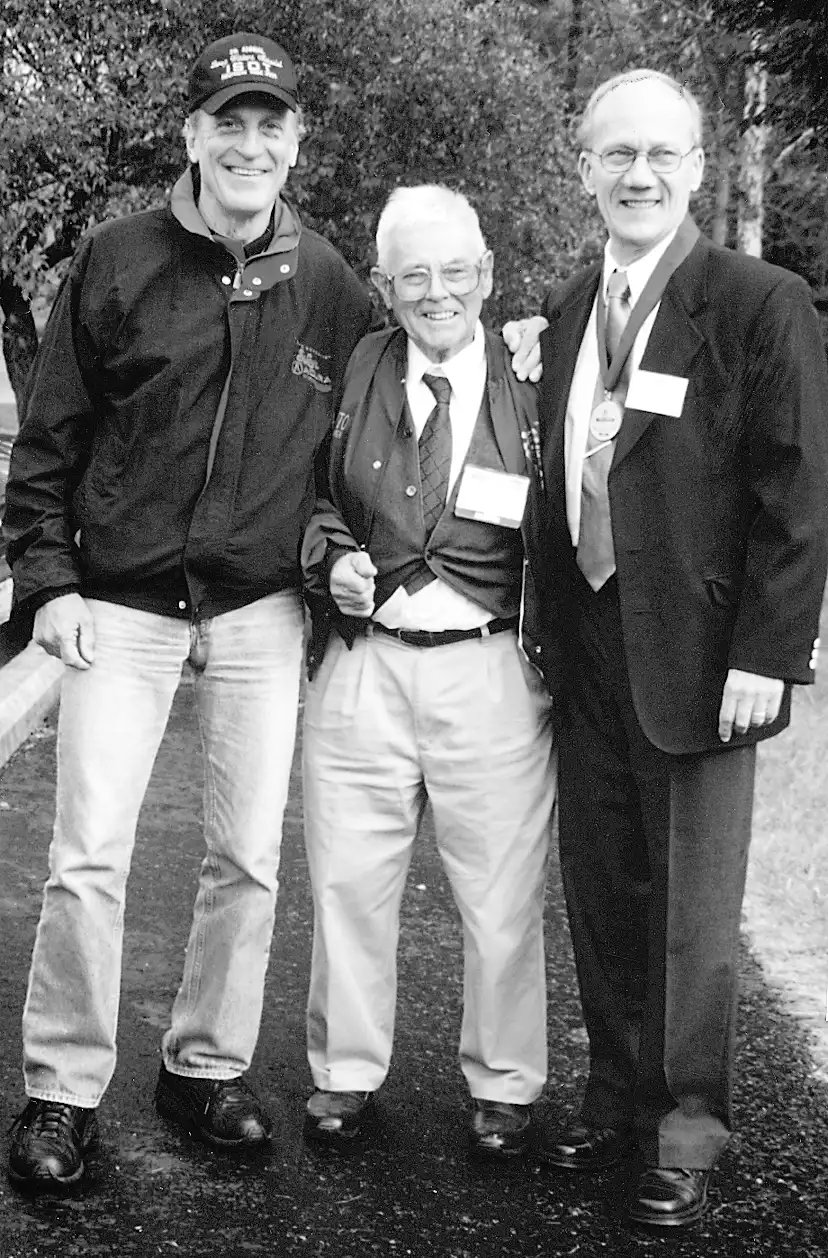

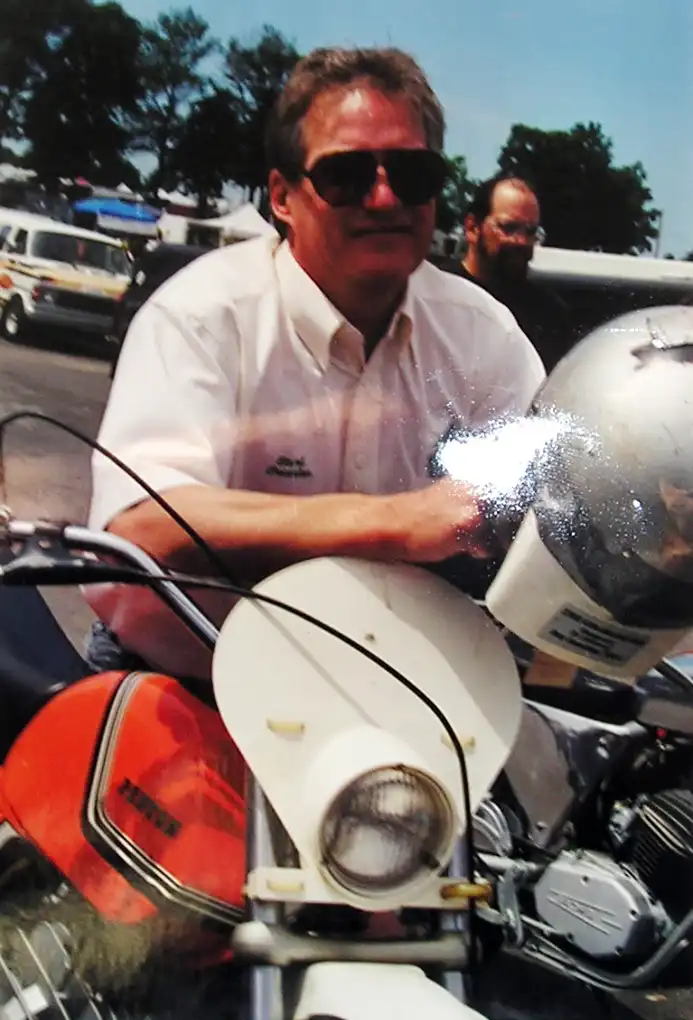

Dave Mungenast was a man of many parts who seemed to earn success at everything he tried. Though he built a business empire in automobile sales and commercial real estate, his first love was motorcycling, and it remained the activity where he maintained his dearest friendships even as he expanded his involvement in other spheres of business. Only now, following his untimely death, is it becoming understood just how much Mungenast achieved as a pioneering motorcycle dealer, a world-class endurance rider, a motion picture stuntman, in automobile sales and commercial real estate, and as a philanthropist who generously supported many national and St. Louis-area nonprofit organizations. His friends and colleagues in one area of his life often knew little or nothing about his activities in another, not because he was secretive, but because he was a deeply modest man who always focused his conversations on the interests and achievements of others rather than himself. Within the greater arc that was Dave Mungenast’s life, the Penton motorcycle might be mistaken for only a footnote. It was one among many brands he rode and sold, and in the nine times he rode the ISDT, only a third of those were aboard Pentons. However, the amount of time he spent in the saddle of a Penton does not tell the whole story. Far more important than his involvement with the brand was his friendship with John Penton that, over the years, became a kind of brotherly love that the most fortunate of us can achieve only a few times in our lives.

Dave Mungenast was born on October 1, 1934 in South St. Louis, an area that had been populated during the 19th century by educated and industrious Germans. High achievement was modeled throughout his family history, including an ancestor who had been one of the master builders of Gothic cathedrals in Europe, and his own father who became a co-founder of the Junior Chamber of Commerce in October 1915. Dave was the fifth among six children, and all of his older brothers earned honors in school, and some went on to achieve distinction in World War II and subsequently in their business careers. To the contrary, Dave earned a reputation as the black sheep of the family, getting expelled from several schools and helping found a motorcycle gang that he and his buddies called “The Dirty Dozen.” Years later, one of them would say, joking, “I think there were seven of us.” Dave’s first motorcycle was a used 1946 Indian Chief that never made it home because he wrecked it along the way, and his first new motorcycle was a 1954 BSA Gold Star. As bleak as his future may have looked to his parents at this time, it was motorcycling where Mungenast found an interest on which he could focus his energy and entrepreneurial talents. Working at Bob Schultz’s shop, he became a skilled mechanic and learned sound business practices, and his preference for off-road motorcycling taught the skills that would eventually earn him notoriety as a world-class rider and Hollywood stuntman.

Dave met Barbara McAboy at Mary Ann’s Ice Cream Parlor, the local teen hangout, in 1953, the same year that he and his off-road motorcycling buddies formed the Midwest Enduro Team. He and Barbara dated for a while, but his half-hearted efforts at St. Louis University were going nowhere and he dropped out to join the Army, signing up for Airborne and the Special Forces, not because he was gung-ho but because it gave him a higher pay grade. In the Special Forces, the previously shiftless Mungenast learned of his inherent leadership ability and gained confidence in his physical skills. In addition to Airborne he became an underwater demolition expert and was later sent to Korea where he was selected as a member of the elite Honor Guard. Dave Larsen, his lifelong friend and employee, says, “In the service, Dave learned how to focus. He returned to St. Louis a different man.” It is likely that being a Green Beret was not the only factor that changed his life, because upon coming home he began to see Barbara again, and married her in January 1959. On April 1, 1960, David, Jr. was born. In addition to being a new father, Dave, Sr. was holding down two jobs and completing a degree at St. Louis University. It was as if Mungenast had made a commitment to leave behind his teenage rebellion to become a good husband and father, building on what he had learned about his character and inherent skills through service in the Army.

One of Mungenast’s two jobs was back at Bob Schultz’s motorcycle dealership. The postwar American motorcycle sales boom had begun, and when Schultz opened a second shop, Dave became general manager of the original store while still performing his duties as a mechanic. Honda had just come on the scene, and Dave was quite impressed with its design and quality. In 1964 Dave won a 24- hour national championship marathon at Riverdale Raceway near St. Louis aboard a Honda scrambler, giving the brand its first national championship in America. He won the event again in 1966. Dave felt there was a great future in motorcycling, and Schultz thought there was a great future in Dave. Schultz tried to get Mungenast to come into the business as a 50/50 partner, but the young father could not come close to the price of buying in. He told Schultz, “I can’t raise that kind of money. I could probably get my own Honda franchise for less than that.” Schultz encouraged him to take this course with his blessings, and in January 1965 Mungenast opened his new Honda store in a small storefront on Gravois Road in South St. Louis. Dave Larsen recalls, “We would uncrate and prep motorcycles late into the night, and by close of business the next day they were all gone.” With success seeming to come easy, by the end of 1965 Mungenast acquired a Triumph franchise to expand his product line. He and Bob Schultz remained fast friends for the rest of Dave’s life.

But things changed as the war in Vietnam heated up. Credit to buy a motorcycle became impossible for any young man with a 1-A draft status, and Dave’s business began to go sour. The Mungenasts now had two young sons (Ray was born in July 1961) and Dave had expanded into automobiles, taking on a Toyota franchise in 1966 before the downturn had begun. Despite the good reputation Honda and other Japanese brands had established with their motorcycles, Americans still did not think much of little Japanese cars, and it became a struggle for Dave to keep his business going and provide for his family. Still, in these difficult days, Mungenast found the time to pursue his personal passion for offroad riding. Edison Dye and John Penton had become Husqvarna distributors, and Mungenast added Husqvarna to his product line. John Penton had met Dave at national enduros, and he recommended to Dye that Dave become a member of a team they were forming for the ISDT that would be held in Poland later that year. Suddenly, Mungenast found himself among America’s greatest off-road riders – John Penton, Leroy Winters, Malcolm Smith, Bud Ekins – and in world class competition. Like any new and unseasoned IDST rider, Dave was over-excited and tried too hard. Smith recalls, “I followed him, and I have never seen anyone crash so many times and still finish.” And astonishingly, riding a Husky that looked like it had been put through a crusher by the final day, Mungenast won a gold medal. He was hooked on the Six Days and set a personal goal of riding ten in succession.

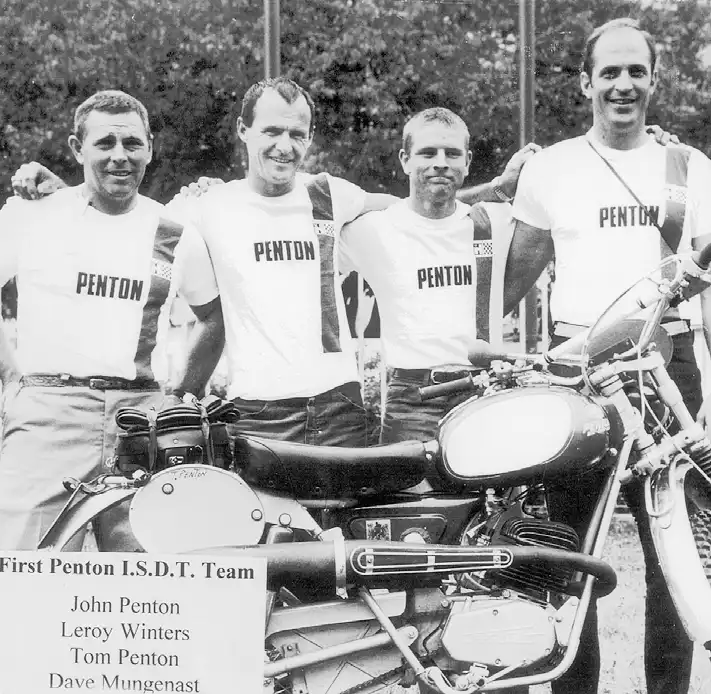

Early in 1968 John Penton introduced his namesake motorcycle, and later that year Dave Mungenast was invited to ride a Penton-sponsored U.S. Vase Team along with John, Leroy Winters, and Bud Green. It may have taught him about beginners luck, because this time he did not earn a gold medal, nor a silver. Still, he finished the event to earn a bronze, which is no mean feat. Riding that year created considerable stress in the Mungenast household because Barbara was pregnant with their third son Kurt, and she was due while Dave was away. But, thankfully, Kurt decided to be late and was not born until Dave returned home. Twice more Dave would ride a Penton at the ISDT, in 1969 in Germany and in 1971 at the Isle of Man. In 1970 in Spain he switched to Husky, which did not bring him luck. It was his first time to fail to finish due to a disastrous crash where he knocked himself unconscious and broke several ribs. For his last two Penton rides he earned silver in 1969 and gold in 1971. Mungenast would ride the ISDT four more times. A factory Honda ride brought his second DNF in Czechoslovakia in 1972, he rode a Triumph to silver medal in the United States in 1973, then for Rokon in 1974 and 1975. In Camerino, Italy in 1974 he earned bronze and at the Isle of Man in 1975 he failed to finish due to injury. There are several stories which prove that Dave Mungenast – just like John Penton – was a true-grit, never-say-die endurance rider. In 1969 Dave separated his shoulder on the first day at the Jack Pine, on the eve of leaving for the ISDT in Germany. A friend took him to the hospital, then said, “Well, I guess we can head back to St. Louis.” Dave said, “No, I have to ride tomorrow, and no one can tell John. If he learns I’m hurt, he might cut me from the team.” During qualifying in 1974, Mungenast broke his hip. Still, he made the team and rode his Rokon to a bronze medal that year. Also, he may be the only man to have won his class at the Jack Pine with a broken leg!

Mungenast never fulfilled his ambition to ride ten ISDTs in succession. In 1976 he failed to qualify for the American team. He probably could have gotten a ride through Canada or Mexico, but he had opened a new Honda automobile store in 1974, and the businesses were still struggling. Later he would see it as providential that he did not ride the 1976 ISDT. He explains, “Otherwise, I would not have been home to take that phone call.” The phone call he was talking about was from an old friend, Stan Barrett, who was pursuing a career in Hollywood. Barrett recruited Dave to do stunt work for several Burt Reynolds movies, including “The End,” “Hooper,” and “Cannonball Run.” Over the next eight years he would also work in “Airport 77,” “Stormin’ Home,” “Harry and Son,” and “Welcome to Paradise” where he and two other riders jumped their motorcycles off of a pier into the ocean. He described the stunt, which earned a nomination for Stunt Man of the Year, as the most frightening thing he had ever done in his life. As a stuntman, Dave got to work with Paul Newman, Jackie Chan, Christopher Lee, Jack Lemmon, and many other stars in addition to Burt Reynolds, and it turned him into a bit of a local hero in St. Louis. The radio and newspaper interviews that resulted from this work put his name in front of the public, and by the time Mungenast’s career in the movies came to an end, his businesses were beginning to turn the corner. His Honda store had become so successful that the company chose Dave as one of only 50 dealers in the nation to open an Acura dealership when the new brand was introduced in 1984. Subsequently, he opened a Lexus dealership in St. Louis and acquired a Toyota/Dodge dealership in Alton, Illinois. Over the years, he developed such a reputation for fair dealing and customer service that his stores almost never advertise. Rather, they rely on word-of-mouth from satisfied customers. Dave, Jr. explains, “today, the only time we do any conventional advertising is when one of the OEMs offers a co-op promotion so good that we would be foolish to turn it down.”

As the three Mungenast sons – Dave, Jr., Ray, and Kurt – matured and took over the day-to-day management of the dealerships, Dave and Barbara began to find more time to devote to philanthropy and community service. They created the Dave and Barbara Mungenast Foundation through which they have supported many charitable organizations. Also, Dave devoted his time and experience to service on the boards of the Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum, the Wheels Through Time Museum, St. Anthony’s Medical Center, and other non-profit organizations. They have been big supporters in both time and money to the Boys’ Club of St. Louis, the YM/YWCA of South St. Louis, and Marygrove, a Catholic organization that helps young people at risk. He has also been chairman of the American International Automobile Dealers Association. Through these activities, the Mungenasts have met with many government leaders, including three presidents: Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton.

Many early Honda dealers who got their start with motorcycles then got wealthy selling cars began to behave as if they were too important to mess with the “lower class” business of motorcycling. This was never the case with Dave Mungenast, and he proved his dedication to motorcycling when in 2000 he opened Classic Motorcycles LLC, a free-admission museum in the very store front on Gravois Road where he had his first automobile dealership. Over the years he had accumulated an impressive collection of rare and beautiful vintage motorcycles, and these have been placed on display along with the collections of other enthusiasts. For example, Bob Andersohn’s amazing collection of steel tank Pentons can be viewed at Classic. The facility often opens its doors to special events, including gatherings for motorcycle clubs. It is under the management of Dave Larsen, who joined the Mungenast organization as its first employee in late 1964.

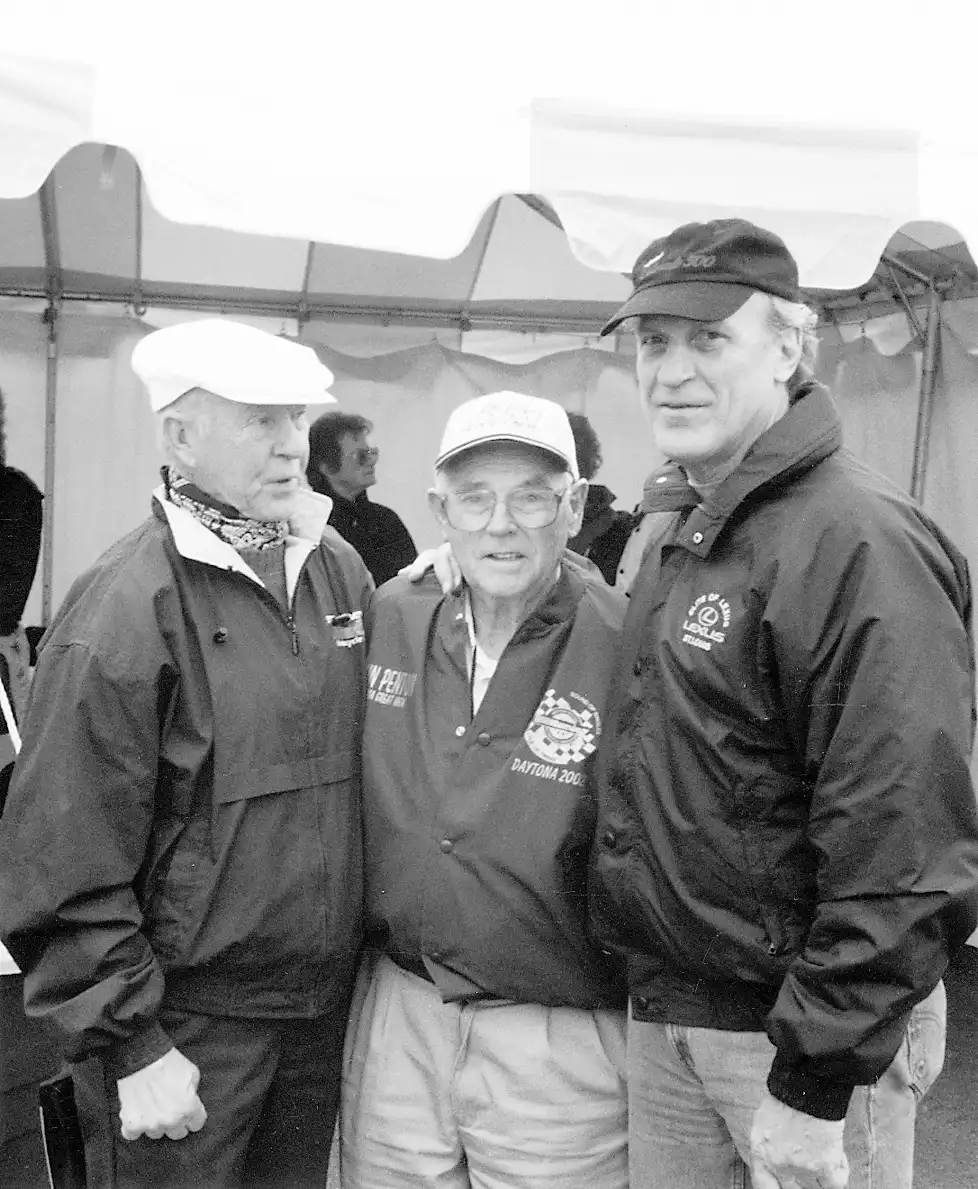

Those who were close to Dave Mungenast understand that yet another chapter of his life was only beginning. With the boys and veteran employees keeping the businesses humming, Dave and Barbara were beginning to enjoy the fruits of their lifetime of work. They had acquired large tracts of land in rural Missouri. On one they had built a retirement home where they raised horses, bison, llamas, and cattle, and hosted their thirteen grandchildren to visit and ride ATVs with Dave. On the other – near Branson – Dave had big plans to restore the old town of Garber as a historical and cultural center. He had other plans for holdings near the Mungenast marina at Lake of the Ozarks. Barbara had been developing her career as a fine artist for many years, and had begun what will be her masterpiece, a larger-than-life patriotic bronze monument that will be displayed at Fort Myer, Virginia. And Dave was finding time to continue his love of off-road motorcycling, riding the Colorado 500, Malcolm Smith’s Baja Ride, and other charity events. By all appearances, it seemed that this man who had accomplished enough for several lifetimes would easily put another ten to fifteen years into his grand plans. Speaking of Dave’s physical fitness, less than a year ago Malcolm Smith said, “At 72, Dave is a man who rides a motorcycle like a good 50-year-old.”

Tragically, early in 2006 Dave began to experience some unusual memory loss and weakness on the left side of his body. But it was with Barbara where the crisis began when on April 26 she had a heart attack. With St. Anthony’s medical center only a few miles from their home, Barbara drove herself to the emergency room, demonstrating the self-reliance she had learned during the years when Dave was away so much pursuing his business and motorcycling careers. It was a mild attack, and the prognosis was hopeful, but three days later additional bad news arrived. Dave had been checked out for his recent symptoms, and on April 29 he was diagnosed with brain cancer. Thereafter, his decline was swift, and in July he was admitted to hospice. Dave died on September 20, 2006, leaving his family, friends, and more than 450 employees still stunned in disbelief. For a period of time during his illness, Dave and the family would accept no visitors. With the typical attitude of a great endurance champion, he was determined to win, choosing to focus all his energy and concentration on the fight. But when he accepted that he would not recover, Dave turned his attention to the friendships that had meant so much to him. John Penton was one of the first people he asked to see, and among the others were Malcolm Smith, John Sawazhki, and other great motorcycling friends.

In 1975, the year when Dave competed in his last ISDT, the Eagles released their hit song “Take it to the Limit.” It became his favorite song, and its title seems to embody the attitude with which he approached every aspect of his life. Whether it was endurance riding, stunt work in the movies, or big risks in business, Dave Mungenast took it to the limit, always doing his best to excel in whatever he did. A biography about his life has just been published and is entitled, “Take it to the Limit: The Dave Mungenast Way.”

Bikes

Dave Mungenast's son Ray founded the Classic Bike Headquarters motorcycle museum in Villa Ridge, MO which includes Penton motorcycles. More info at https://classicbikehq.com/

The Mungenast family also has Pentons on display at their dealerships in St. Louis, MO. More info at https://www.mungenastmotorsports.com/

Member Profile

I was born in Auburn, CA. and was raised in Loomis, CA.on a 40 acre fruit ranch. I have four brothers, Richard, Edward (deceased), Frank, and Donald and two sisters, Linda and Donna.

At 7 or 8 years old, I was driving vehicles on the ranch. We had an orchard truck, which was a Ford model A flat bed truck, a farm tractor, and caterpillar tractors. I would work tilling fields, cultivation, and digging ditches around trees. The trees were irrigated and the ditching was important in getting the water to each tree. We grew peaches, plumbs and pears.

At the age of 15, I was working one of the local farms making wooden crates (400 to 500 a day), I would dump the fruit on the conveyor belt and the women workers would pick though the fruit and pack them into baskets. The baskets would then be put into the wooden crates. I would load the boxes onto a flat bed truck and take them to the fruit shed in Loomis for transport by rail.

My first motorcycle was a 1947 Cushman Eagle – I couldn't keep it running. That was around 1953. It had a 2 speed shift on the side. I paid for it from the money I earned working the ranch and neighbor's farms. I was 12 years old at the time. I would drive it all over the place when I could get it running.

I graduated from high school in 1959 and I was working for my uncle in construction building homes for about year and half. I got married in 1960 to Joyce. We had 5 children, all girls, Roxanne, Julie, Carrie, Kimberly, and Marcey.

After working the construction job, I went to work at Aerojet, a manufacturer of rocket engines. I started out doing plating and chroming, then later I became an inspector for the rocket engines using magaflux and die penetrant – checking for cracks. I worked there for about 4 years, then Aerojet had a massive layoff, and I was let go.

In 1964 I got divorced and joined the merchant marines where I traveled to the orient, South America, and Alaska, on an oil tanker. It was very hard work. I would go out for 3 months, come back 3 months and then pick another ship. Over time you would build up seniority. I did this from 1966 to 1969. While home on leave I would race motorcycles. It was one of the best things that I did in my life. I was very good at racing as long as I didn't fall off, however working on the ships for 3 months slowed up my racing career.

The local motorcycle shop in Loomis was Genes automotive Suzuki. He opened this shop in 1961 strictly for automotive repair. In 1964 he became a Suzuki dealer. He was one of the earliest Suzuki dealers in California. Lars Larson set him up as a Husqvarna dealer in 1967 and then Pentons. I hung out there all the time. My first real bike was a brand new 1965 Hodaka Ace 100. I stripped off all the lights and made it into a race bike. I raced all the races 2 times a week – mainly TTs and rough scrambles. I rode for a couple of years until 1967 when I started riding a Husky 250s in TTs, rough scrambles and then MX. I was a shop-sponsored rider for Gene. Bill Onga was Gene's chief mechanic, who won the 1969 Elsinore Grand Prix. So, Gene was a good rider and an excellent mechanic. Gene and Bill prepared the bikes and I rode them. Gene and I were good “mud runners”. I purchased my motorcycle at their cost and they would prepare it. Sometimes they would have a different bike for me to race. I raced mostly Huskys until the Penton motorcycles arrived.

In 1967 I was one of the 12 founding members of the Dirt Diggers M/C club in Northern CA. The club is still going on today. I went to the 49th consecutive national Hangtown MX this year. We put on the first Hangtown MX race in January 1969. We had all the top riders, Gary Bailey, Dick Mann, John DeSoto, Ronnie Nelson and others. We offered a larger purse than what the AMA would offer for their nationals, so we went outlaw. This was a big money looser for the club as it rained (really bad weather) and we had to pull all the spectators cars out of the mud after the race. We made up for the loss later in the year where there was better weather and a much bigger crowd. Next year will be the 50th anniversary of the Hang Town race.

Before the Penton motorcycle, I worked for Aragon Distributing in Monrovia, CA. They sold motorcycle accessories and I worked as a salesman for them. My sales area was from Reno, Nevada to San Jose, CA. I worked there from late 1968 to early 70. During this time period my leg got busted by Donnie Emler, the owner of FMF Racing at Mammouth Mountain MX track. (Donnie built motorcycles and was a great tuner which led him to building exhausts). I was riding my Penton leading the pack and I fell in an off camber turn. Donnie was on an American Eagle and ran over my leg while I was picking my bike up. This put my racing on hold until I healed up. I still did my work at Aragon during the time it took my leg to heal. That was one of the many bones that I had broken during my racing career. Back in those early years, there was very little protective gear to wear for racing.

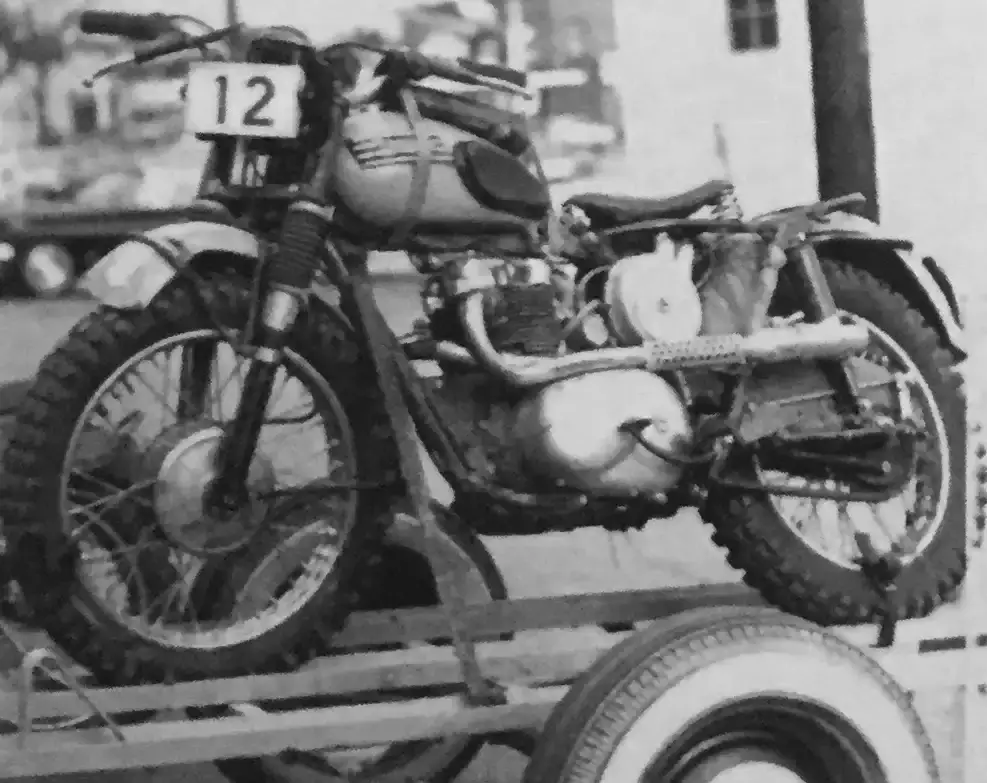

Lars set Gene up with the Penton franchise (in 69). They then provided Penton 125 steel tank Pentons for me to ride.

Lars handled the NW distribution of Pentons out of El Cojone for Torson Hallman Racing (now called THOR) for a short time until they they decided that they only wanted to sell clothing to the dealers. The distribution of the Penton motorcycles was then picked up by Fred Moxley some time in 1969, located in Medford, Oregon.

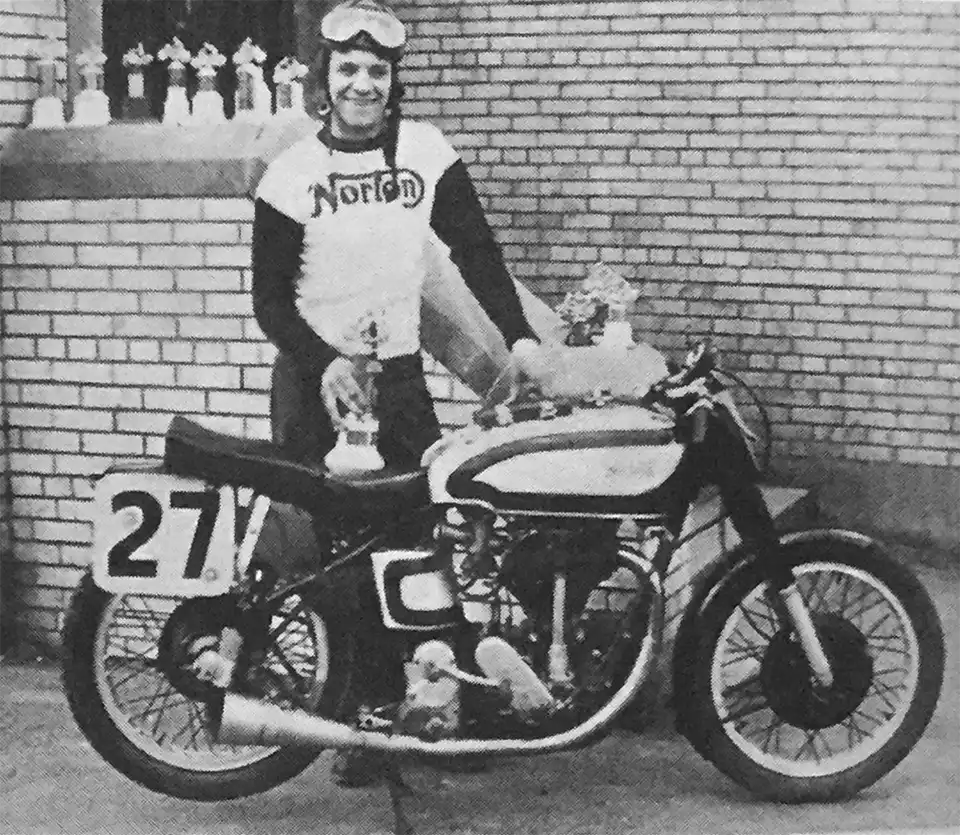

In 1970 Fred Moxley brought Penton motorcycles from Medford, Oregon to Sacramento for west coast distribution in California, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Nevada, and Montana, This led to a better ride for me, for I was now sponsored by Fred Moxley. I received no money, just a new bike to race. I won a lot of trophies. I rode for fun and got to go to a lot of places to race MX, enduros, cross country, and desert races. There were a lot of desert races in Nevada that I went to. I shied away from MX races because you mostly waited around for your class to race. In desert racing you rode for 3 or more hours straight. I rode a lot of desert races and enduros. I began to like riding most of the day and not waiting. Even though I was still riding Pentons, I also rode Puch 125s.

There were 2 different distributors for Puchs on the West Coast – Ted Lapadakis and John Penton for a brief time. In 1972 or 73 I was working for John Penton selling Puch 125 & 175s. They were good and fast and I set up a lot of dealers with them. There was a war going on with them (Puchs) here because of the 2 distributors. Ted Lapadakis was both Puchs and DKW distributor on the West Coast in Southern Cal. DKW was Penton's biggest competitor on the West Coast.

In 1970. I was hired by Fred Moxley as a parts warehouse manager. I was then put on the road as a Penton rep for the West Coast, setting up new dealers and servicing existing dealers. In 1973 I was brought in as assistant manager for the warehouse. Fred taught me the whole business.

The warehouse was stocked mostly with just parts and accessories. There were rarely any Penton motorcycles in stock. The bikes were sent from back east to the trucking companies in containers. Fred and I would then go to the trucking company, open the containers and then put shipping labels on the crated bikes for shipment to the dealers. West Coast Dealers were always complaining because they could not get enough Pentons to sell especially the 125s. When the 250s came out we had some of those initially stocked in the warehouse.

We had Wassel Mudlarks to try and sell on the west coast. We had trouble selling them here just as John had trouble selling them back east. We would set up new dealers with the “package deal”. John did not load us up with them. We had no more than 40 or 50 and this allowed us to get rid of all of them pretty fast.

I first met Carl Cranke at 3 Sar Raceway in the Sacramento neighborhood where we raced dirt track. Carl was sponsored by Marion Pyle (called the “Big O”) Orangevale Motorcycle Center in Orangevale, CA. I was a novice and Carl was working his way up to becoming an expert. We would see each other at all the races. Because of Carl's reputation as an excellent mechanic and go fast racer, Fred hired Carl in 1971. Carl wrote technical manuals and would troubleshoot problems for dealers. He had a whole service shop set up for this. We took good care of all the west coast Penton dealers. It was Fred who recommended Carl to JP to consider him for become a Six Day rider.

In 1974 my life changed when I got custody of my kids. This was also the same time when the deal was made to turn over distribution of the Penton motorcycles in CA. to KTM.

Fred decided to leave and he opened a Mexican restaurant in Oregon. Fred mentioned me to John Penton to take over the warehouse operation (in Sacramento) for Hi-Point products. There were no more Penton Motorcycles to be sold on the west coast, they became KTM motorcycles. The distribution of the KTM motorcycles and parts was taken over by Ted Lapadais at his warehouse. This was a confusing time period. At the races there would be bikes branded with KTM and some with Penton. Some racers would remove the KTM decals and put Penton decals on their bikes. Other racers would remove the Penton decals and replace them with the KTM decals.

I had the opportunity to attend nine ISDT events as a support rider and working the check points for the Penton Six Day riders. John paid for all my travel expenses to these events. KTM would supply a bike for me to ride. The reason I was able to go to all of these Six Days events was because of my Sales manager Bruce Young. He was my right hand man. He would run the business for me during the 3 weeks that I would be gone.

My very first Six Days event was Camerino, Italy in 1974 where I got to be with all the Penton riders, Frank Gallo, Kevin Lavoi, Jeff Hill, Danny Young, Dave Mungenast and Paul Danik. I had a ball and so much fun at all of them. Previous to the 1974 event, I rode ISDT qualifying events in McMinnville, OR and Bad Rock, OR.

John owned a small car, I think that it was a Fiat, that he kept over in Austria and he would use it to drive around to meet with the manufacturers. I got to go to a lot of places with John in that car after the Six Days events in Europe were over.

I was with John Penton when we met the owner of HIRO. We went to lunch with the owner of HIRO when John made the deal to buy the HIRO motors.

I went to Alpinestars with John and we stayed at Santi's house. Santi did a lot of the designing of the boots himself. The boots at that time were made at his factory in Italy by a lot of women at sewing machines.

I went out to dinner a couple of times with John and Erik Trunkenpolz. Erik was a very quiet guy.

I stayed at Kalman Cseh's house once. Kalman would do the language translation for Erik Trunkenpolz and John Penton. When Kalman left KTM he became a distributor for Scott. He had a warehouse in Austria and I got to tour it.

John did all of the driving in that small car and he drove it fast. I remember us pulling into Paris one night and parking near the Eiffel Tower to get some sleep. It was all lit up and I was all excited looking up at it. I told John that I wanted to go see it in the morning and John said OK. The next morning I woke up with us traveling down the rode and I never got to see it. Traveling with John was straightforward. When we stopped for gas we would buy something to eat. If John would get tired, he would pull over off the road and take a 10 minute nap.

I was at the KTM factory several times. I took photos of the conveyor system where there would be moped and bicycle parts traveling along the assembly lines with Penton motorcycle parts. Drinking beer for lunch and on breaks by the employees was acceptable behavior over there. There were even beer vending machines in the dining hall. I find it funny that there were many times when we would open up a bike crate in California and find beer bottle caps inside.

I became the General Manager for Hi-Point Racing Products when KTM took over the motorcycle distribution. We sold all the Penton/Sachs parts off to dealers in bundled deals. All the brochures, and manuals went into the dumpster. Most of the parts for the KTM powered Pentons were sent back to Texas or Ohio warehouses. There were no motorcycles in the warehouse.

No motorcycle parts or inventory were sent to KTM's new warehouse in Southern Cal. We (the West Coast operation) were officially out of the Penton business and into only the Hi-Point business.

When I took over the Hi-Point warehouse, I started making t-shirts, green and gold Penton leathers, jersies and many other items that were sold exclusively on the West Coast. The clothing lines were a good thing for us. The West Coast warehouse was in debt to Penton East (for things like rent and it's share of advertising) and we were able to pay them back what we owed them.

I would go to meetings at the Penton Lorain warehouse to meet with Larry Maiers, Matt Weisman, Elmer Towne, and other key employees to discuss what items were needed. We talked about what we were going to do and this is how many new products were added every year to the Hi-Point catalog.

When I would travel east for the meetings I stayed mostly at Matt and Barb Weisman's house. Sometimes I would stay at John's house and other times at Elmer and Kathy Towney's house.

I met Teddie Leimbach at some Six Day qualifiers and I would see him on these East Coast visits. I was at the Lorain warehouse in 1980 the day that Teddie was in the car crash with the truck. He was a very talented rider. I went to dinners at Pat and Paul Leimbach house during some of these visits also.

I had met Ted Penton back when Fred was distributing the Penton motorcycles and would also see him on my trips to Lorain, OH. He would occasionally show up at the Sacramento warehouse. He was a character. I got to see the prankster side of Ted Penton when he came over to California. We went on a tour of the ship, the Queen Mary, in Long Beach. During the tour we were escorted down into the engine room. When the tour guide continued on, Ted stayed behind and was trying to get one of the engines to start. He did manage to get some of the lights to come on before the tour guide came back and chased us out.

I remember being at a Hi-Point sales meeting in Lorain, Ohio. Larry Meiers, Matt Weisman, Elmer Towney and many Hi-Point employees were there. So here we were discussing products when John walks in. He was wearing his standard uniform, a green sweater, grey pants and mason shoes. His sweater was burnt, his eyebrows and hair were singed. The hair on his hands were also singed and he had an odd look on his face saying, “you would not believe what just happened to me.” He was at one of his properties where he had natural gas wells. He was looking down into one of the wells and lit a match. I'll leave it up to your imagination as to what happened. It is a miracle that he did not get seriously burned.

John would have an auditor come out once a year to audit our books. When I ran the warehouse I did it like I owned it. I was frugal with all my expenses with no extravagant spending.

Hi-Point Products sponsored riders like Danny Magoo, Kenny Roberts, Bob Hannah, and Ricky Graham to use Hi-Point products and show the Hi-Point logo on their clothing.

Boots were the most popular item that we sold. We could never get enough and they were back ordered all the time. The crazy thing about the boots was even though they were a big seller, there was very little profit margin in them.

Other popular items were the Hi-Point oils, jerseys pants, gloves, plastic fenders, tires, and Sun rims. We sold a lot of most of the items that were listed in the catalog. There were unique items shown in the catalog that were developed from back east, such as folding shift levers, enduro equipment, magnifying glasses (for holding a pocket watch), route sheet holders, tank bags, and tool bags. Heavy duty inter-tubes were a hot items for us. We would set up a display at the annual Long Beach dealer show to showcase the Hi-Point products.

In the early 80s my partner and I built the building we were in and it was our 3rd move. The space was shared with my partner's business. Like the other two buildings, there wasn't enough room for all the new products that kept arriving, but we made it work.

When I built the warehouse. I had to build a special room to house an IBM 3200 computer. It was a huge piece of equipment that was noisy and needed to be air conditioned. I had a couple of great gals that knew how to run it. It's hard to imagine that today's cell phones are faster and have more memory and computing power than that IBM.

I knew Malcolm Smith back in 1971 when he was working at K&N. I would see him at races, qualifiers, and dealer shows. We always called Malcolm “smiley”.

In 1988 Malcolm Smith made a deal to buy the Hi-Point product line. The deal consisted of all the existing inventory except the obsolete Sachs stuff that was still around. I worked for Malcolm running the warehouse. Since I owned the building, Malcolm became my new tenant. I ran the whole business for him, buying the products and paying the bills. I would attend regular meetings in Riverside where I would meet with Malcolm and his sales team.

Malcolm had 3 key people, Wayne Cornelius, Jimmy Lewis, and Gary Drean.

Drean was the computer guru and accountant. He supplied new computers for my warehouse when Malcolm took over. Gary flew his own private plane from Riverside to Sacramento to deliver and set up the computers.

Wayne Cornelius was product manager for Malcolm Smith in Riverside. He was a smart designer. He came up with fancy gear, and got us into water sports clothing. Malcolm Smith Racing Products made a re-surge in sales because of this. We got involved with some splashy stuff with the Jet Ski craze.

Jeremy McGrath was sponsored by Malcolm under the Hi-Point name in 1988 before he got picked up by Honda. He was discovered at Mammouth Mountain MX, a ski resort in the mountains NE of LA. This is a big event held every year in June. Riders at that time, who were under motorcycle company contracts, generally were allowed to obtain clothing and gear sponsorships of their choosing.

In 1990 an Asian company (corporate raiders) made a deal with Malcolm to buy Malcolm Smith Racing Products. They took out huge loans on the business and payed themselves lavishly. Their dishonesty wound up driving Malcolm Smith Racing Products into bankruptcy. Rocky Cycles (known now as Tucker Rocky) wound up buying the business at auction. What was left of the inventory at my building was moved to the other warehouse buildings in Riverside and that was when I left.

I ended up selling my half of the building to my partner. I did not do anything for a while. I worked for about a year for a friend installing car alarm systems in new cars for dealers.

I then went to work at Seafood Suppliers, Inc. a wholesale sea food business owned by Bill Dawson, who was one of the founders of the Dirt Diggers. He owned a warehouse right on the docks in San Francisco. I commuted to San Francisco for this job staying at his home during the week and traveling back to my house on the weekends (a 2 hour one way drive). His business consisted of buying fresh caught fish from the fishermen, at their boats at the docks. The fish were then taken to his warehouse where they were cleaned, filleted and packed. His customers were all distributors who sold to restaurants. For this type of work, the day generally started at 4 am. I handled the sales, talking to customers, and kept track of the inventory.

To meet our customer's needs, other varieties of fish from the East Coast and Canada were air freighted in, along with oyster and clams from Boston off Cape Cod. Air freighted shipments had to be picked up at the airport to meet our customer's requirements. This would become nerve racking when there would be flight delays.

I did this job for about 2 years. Bill was having some problems in running his business and making a profit. He was in debt and I helped to get things in order and pay off the debt. This was a fun interesting experience for me.

I then went to work with my brother, Frank in construction – mainly fire restoration. I worked in the office with him for about 2 years. It was a very successful business that was sold to our nephew. It involved mostly insurance claims. We were basically fire truck chasers. We would find out where the fires were at and go there before the fire trucks left. We dealt with home owners who were panic stricken and in a state of shock. We would explain to them what was going to happen and that their insurance company would be paying for their stay in a motel until their house was fixed up. We would then get their permission to board up the house. We would then get back to the homeowner with a price quote to fix the house back up. In most cases the insurance company would approve our quote and we would get the job. It was a dirty business, dealing with smoke damage and soot, but it was a fun business.

Up until just recently, starting in 2000, my younger brother Donald and I were buying houses, rehabbing them and then reselling them. My brother was the genius. He had years of experience as a carpenter dealing with dry rot. He could do everything, carpentry, electrical, plumping, drywall, anything and everything except carpeting and roofs. We kept some of the rehabbed properties to rent. We are now down to one last one. He had the talent and I had the money. We focused mainly on foreclosures, bank owned and condemned houses.

I became officially retired in 1999. I did all of these and other things to keep busy and make up for the retirement plan that I never had.

I found out about the Penton Owners Group from Bruce Young at Western Power Sports. I joined in 1999 (member no. 230). I think that it is pretty neat.

I was at the 2000 AMA Vintage Days event at Sears Point where Penton was the feature marque and John Penton was the Grand Marshal. That was a great time. I remember John taking the parade lap around the race track and going the wrong way. I hung around the booth talking with Matt Weisman and even helped sell T-shirts one of the days there. I remember it being a good size event. There was also a cook out at a city park one evening. That Vintage Days event was also the last time I met Jim Pomeroy.

Todd Huffman did a very good job with the making of the John Penton movie. He did an hour and a half interview with me in California and I am in the movie twice for about five seconds. When the movie came out, I went to two of the showings at the movie theaters. One was in Sacramento the other was in Placerville, which used to be called Hangtown before they changed the name. In watching the movie I learned some things about John Penton that I did not know. After traveling with him all those times and being at meetings with him I thought that I knew all about him.

I am blessed for being involved with motorcycles, the racing and all the wonderful people that I worked for and was involved with. Without these contacts I would never have been able to travel to Europe and meet some of the people involved in the motorcycle industry. This was a great experience for me during this lifetime. I wouldn't trade these memories for anything.

by Alan Buehner

In my conversation with Penton owners for the past several years, most people would ask about John Penton during the conversation. For some strange reason, during many conversations I would have with West Coast Penton owners the name Carl Cranke would be the first name asked about. During some of the monthly meetings, I had heard about Carl and what a talented rider he was, but I never expected him to have the following that he does. I met Carl for the first time in April at the AMA Vintage Days event at Sears Point where “Penton” was the feature marque and he took time off, away from his family to join us at the event. The following is a little background on Carl and some of the stories that he shared with us.

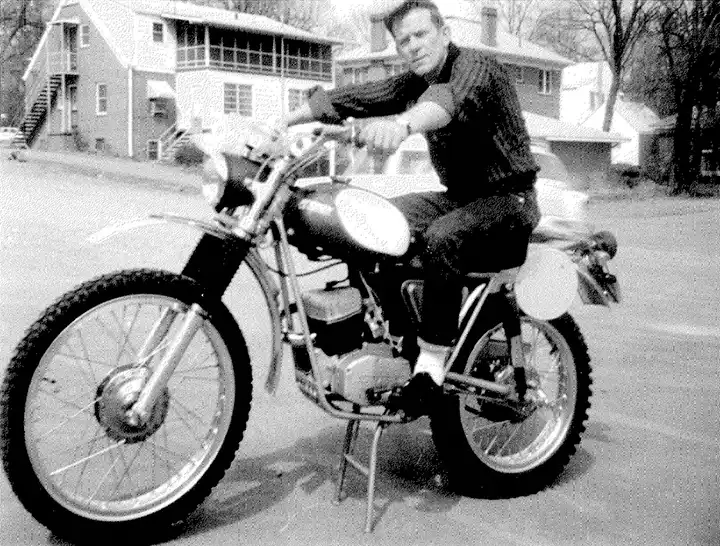

Carl Cranke was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana and raised in northern California. He was a quiet kind of kid while growing up but that all changed when he discovered motorcycles.

My first bike.

“While I was going to high school in 1964 there was a motorcycle shop along the way to and from school. It was Orangevale Motorcycle Shop that sold Suzuki, Triumph, Greeves and Maico motorcycles. In order to hang around the shop and get to know more about these wonderful machines I offered my services to help out in doing anything. The owner, Marion Pyle, gave me the job of cleaning the cosmoline off of the new bikes. This was coated on the bikes to protect them from the elements during shipment. No one at the shop enjoyed this chore but I eagerly jumped in to do it. It was a messy job that required using a solvent to remove all that sticky goo from the bikes, but it got me into the back part of the shop where I could see all of that things that go on with fixing, repairing, and building bikes.”

“After a few months they put together a specially tuned 50cc Suzuki for me to ride at 3 Star Raceway, the local dirt track which was a 1/10 mile oval flat track. In those days, the novice riders were lined up on the front line. As riders would show their skills by winning races, they were moved back to the next row behind the novices. The more you won, the further back you were placed for a starting position with the best riders on the back row.”

“So there I was at my first race on my very own race bike and I never told any of the guys at the bike shop that I never even rode a motorcycle before.

“At the next race I was put on the second row because of my win at the last race. This meant that I would have to pass the riders on the front row and I told Bob Taylor that I did not know how to pass and I asked him what I should do. He took me out onto the track with my bike and placed it on the outside berm. “This is where you ride your bike. Keep it wide open until you pass everyone” he told me. So, that is what I did. I put the bike on the outside cushion and rode it all the way around the track. I had a couple of tight squeezes when I passed some riders who were also riding the outside edge and I somehow managed to get between them and the fence.”

“I always rode the cushion and I did it with the throttle wide open. My bike was so fast that I won every race for the rest of the season. The more races I went to however, I did notice that the bike was becoming a little harder to control if I would let up on the throttle and I would have to make sure that it was kept wide open to prevent that small bike from bogging down. I found out later that Bob was gradually upping the gear ratio on the bike for each race I went to. This is how I learned how to race dirt tracks”

Carl, you won many dirt track races, what brand of bikes did you ride.

“I was riding Suzukis, Triumph, Bultaco, & Jawa. My favorite bike was a special Triumph Cub short tracker.I liked Bultaco for TT and scrambles.”

Where did you do your short track racing?

“I raced all over northern California and southern California. In my pro novice year, 1968, I was the HiPoint novice shorttracker in the nation.”

You competed in desert races. What brand and sizes of bikes did you ride and which was your favorite brand and size?

“My first desert race I rode a 73cc Sachs. I loved to ride Pentons later on in my career. It was great to win overall on a 125cc bike.”

You then moved into riding MX. What brand and size of bikes did you ride and which was your favorite brand and size?

“I rode motocross because I could ride three classes (125, 250, open). That was 9 20 minute motos in one day! At first I rode a DKW 125 (before Penton). In the 250 class, CZ was my favorite! In the open class I rode either a 360/380 CZ or sometimes a 400 Husky. That was a trick switching sides shifting as you rode 9 motos.”

It was Carl’s early experience with Bob Taylor, a mechanic at Orangevale Motorcycle Center, that he learned not only how to ride but how to repair motorcycles and make them go faster. Bob taught him the tricks of how to port the cylinders of motors. Carl was always known for never leaving home without his grinder. He was the master at taming the KTM 250 motors to make them more powerful and controllable.

The Penton experience

“In 1971 the West Coast Distributor was after me to ride a Bultaco at the local tracks. I did not like Bultacos and I turned him down. I had my eye on riding a Penton. I went to the local dealership and asked them to sponsor me with one of the new Pentons to race at the local MX tracks. They turned me down because they were sponsoring another rider. I was upset with being turned down and decided that I would have to prove myself by beating their Penton rider. I took advantage of the Bultaco dealer by accepting his offer to ride the Bultaco. I raced it once at the next MX race and won. I went back to the Penton dealer and they gave me a Penton to ride. That was the last time I ever rode a Bultaco.”

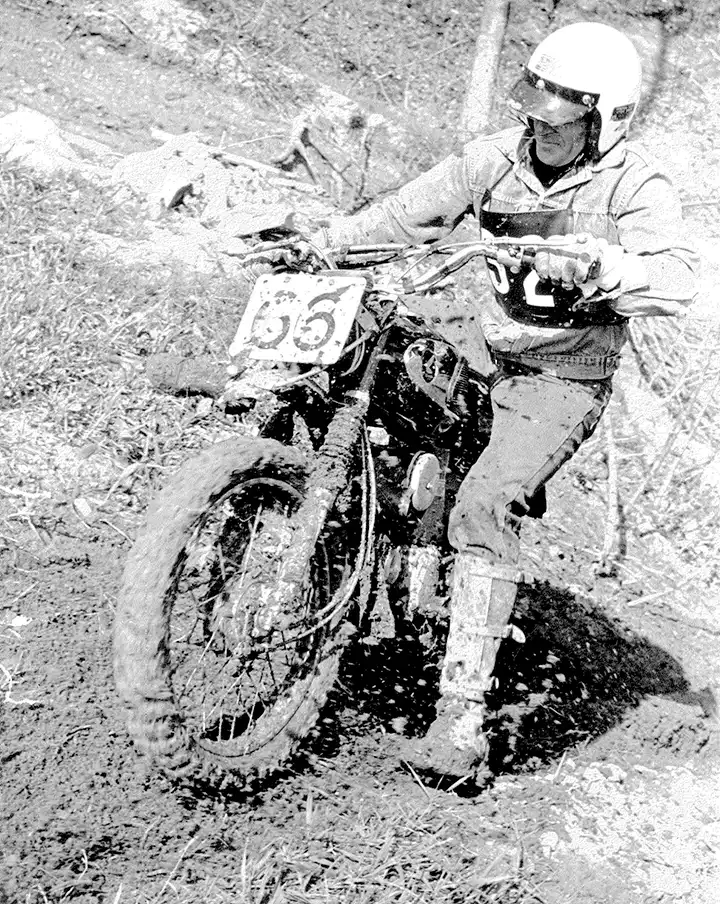

“In early 1972 I read about the I.S.D.T. events and had a desire to compete in it. Fred Moxley of Penton West contacted John Penton about my desire to ride the qualifiers for the upcoming ISDT event and what a talented rider I was. John had doubts about me because I was one of those California riders. John knew California riders could ride in the desert but that they did not have the skills to ride the woods, water, and mud of the Enduros in the east. Fred persisted and John agreed to meet me and check out my riding skills. When I met John for the first time, John knew that he was wasting his time and I became known as that long haired hippie from California.”

“I was given a new 175cc Puch by John to ride in the last 2 day qualifier of the season in southern Ohio. It was a nasty event with lots of mud holes. Out of 200 starters, only very few riders finished the course. I was one of them and I came in 2nd. Only two gold medals were awarded. Carl Bergen on a 250 Husky came in first and I on my 175 Puch. John was impressed (since he knew that there was no way I could finish the event let alone win, riding that bike) and he gave me a place on the 1972 Trophy Team. That Puch was a piece of junk. Before I rode it in the event, I pulled the motor apart and ported it out to obtain all the power I could out of it.”

Carl qualified and went to his first I.S.D.T. event in Spindleruv Mlyn, Czechoslovakia where he won a Gold medal riding the 125cc class.

Carl shared a story about his experience at the Isle of Man, England event held in 1975 during which he was riding a Penton in the 350cc class.

“1975 was the last year where on the sixth day the special test was a road race run on the city streets and riders rode their bikes equipped with knobby tires. All of the following Six Day events had their special test run on a natural terrain course and run as a MX race.”

“Jack Penton rode the special test first. I asked him how the course was. He said that it was OK and that I should have no problem taking the corners because the knobby tires would slide around the turns just like dirt track racing.”

“I grabbed the lead in my race. At the first turn I set the bike up and gassed it to slide around the turn. The bike kept sliding and I wound up going up and over the curb. Behind me were two CZ riders on their Jawas. As I jumped the curb, I remember them riding by, you know their riding style, sitting straight up even in the turns, riding side by side. As they negotiated the turn, They turned their heads to watch me hit the curb, then turn their heads back to continue on their way. When I saw them the way that they looked at me, I could sense what they were thinking (typical American rider, careless and rash with no sense of consistency). This embarrassment motivated me to turn this road race into a flat track and catch up to these guys. I pored it on and soon caught up with them at another turn in the course. They were riding side by side when I went around them on the outside, tucked in, sideways, Freddie Nix style.“

Carl was the only American rider to win that special test. He took home a Gold medal

On July 8, 2000 Carl Crank was inducted into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum in Pickerington, Ohio.

See Also

Carl Cranke Remembered: Stories From His Friends

Videos

Related Tech Tips

CARL CRANK PORTING SPECS for 100 and 125cc Sachs Cylinders

Misc

MY FIRST “REAL” MOTORCYCLE

by Al Born

Originally printed in the 2002 issue #15 of Still….Keeping Track

I received my introduction to motorized 2 wheelers in the summer of 1946 on my cousin’s new Whizzer motor bike. I was 12 and he was 13 at the time and even though this was a real genuine Whizzer with heavy duty spokes and such, my memory says that we pretty much rode it to the ground that summer. There is a lot of hills down there in West Virginia and even though that Whizzer ran pretty good, we still did a lot of pedaling, especially when we were riding double. Anyway, it was a lot of fun and I guess you could say that I “was hooked”. We rode that little Whizzer until it finally died near the end of the next summer. Then I just dreamed of owning a “real” motorcycle some day. I graduated from high school when I was only 16 years old and could not get a good paying job at that age. So, I guess you could say that I just kept on dreaming as I sure couldn’t afford a “real” motorcycle.

During the summer of 1952, one of my friends who was a couple years older than I bought a 1946 Indian. It was a large one with a 2 cylinder engine that was hard starting and very heavy. We pushed it a lot and rode it a little in some way or the other. It also damaged my cousins barbed wire fence (with her on it) and tore up about a half acre of my Dad’s corn field when it got away from my friends younger brother. In September of ‘52, my friend went into the Korean war, so the next month I came to Ohio for a better job. I went through some hot-rod Mercurys for the next 3 or 4 years, but the yearning for a “real” motorcycle never left. I finally got a good job at Ford in January of 1955, so I was soon thinking of getting my own two wheels with a motor. One day I was driving up Elyria Avenue in Lorain and there in a used car lot sat a pretty, blue, 1951 125cc Harley Davidson with a “for sale” sign on the windshield and I knew I had to have it. So, I used some of the money I was saving for my next Mercury and I became the proud owner (at least I thought) of this pretty blue Harley. Well, it just didn’t turn out to be the “jewel” that I thought it was. It had wiring/ ignition problems that I just couldn’t get all straightened out, so I spent some time pushing this “Dream Machine” too. The only good thing about that little Harley was that it pushed much easier than that old Indian that we had pushed around in those West Virginia hills. Thank goodness, fall finally came and I put that little Harley in the shed for the winter. Around February 1956, a guy at Ford that everyone called Cowboy and I were talking one day and he said that he had a 1949 45ci Harley with a 3 speed transmission that he wanted to trade for a small motorcycle. I began thinking that here was my chance to unload my pretty blue Harley. The “catch” was that his motorcycle had back-fired through the carb and caught it on fire. It had burned the wiring, seat cover and pad, rear tire as well as melting most of the paint from the gas tank. He led me to believe that I was getting a good deal, as the parts wouldn’t cost too much. So, we traded even up. I went to work and painted (by hand brushing) the gas tank while waiting for the wiring harness to come. It finally came and when I put it on, it started right away. It would start real easy when it was cold but not when it was hot. I soon discovered that the carb adjustments were warped from the fire, so I usually rode with one hand on the carb turning the adjustment screws, trying to keep it running half-way decently.

One evening Ralph Haslage came over to my house and he was riding a beautiful 650cc BSA twin. He took me for a ride and when he changed to second gear, my feet went up past his head and I knew for sure that this was a “real” motorcycle and I had to have one. The next evening Ralph and I went to Penton Brothers Motorcycle shop and they had a nice 1955 BSA 500cc twin. I talked to Elmer Reichart about trading in my Harley which he didn’t seem interested in at all. About that time John and Ike came into the shop and when Elmer told John about my Harley, he just laughed and told me that if I wanted the BSA I would have to buy it without a trade, which I did that night. That BSA became my first “REAL” motorcycle as far as I was concerned. I rode it a lot that summer and all of the next year which was 1957. Back then the motorcycle shop was open on Friday nights and a lot of guys spent their Friday evenings there talking motorcycles and drinking coffee with John, Elmer and sometime Ike and Ted would drop by as they were running the Machine Shop at that time.

In the late summer of 1957, Ralph took me to a Scrambles race at the Meadowlarks track in Amherst, Ohio. My most vivid memories of that day was seeing George Singler broad-sliding his BSA around the sharp turns while standing up. I had a problem believing what I was seeing. I remember telling Ralph while on the way home that if I could ride a motorcycle like George did that I would be the happiest guy in the world. Needless to say, George became my motorcycle hero on that day.

In the winter of 1957 and 1958, a group of us from Avon, Lorain, and Elyria organized the Avon Cycle Club which was in existence for 7 or 8 years. We rented a farm on Lunn Road in Strongsville and proceeded to build a Scramble track. One Saturday after we had finished grooming the track for our first race, the guys that had their scramblers there decided to have a little race to check out the track. I joined them with my “real” BSA street bike and to my surprise, I beat them all. My bike did have a nice set of STS tires which worked nicely on that track. Anyway, after that little deal, I knew I was hooked on racing and that there was no way out. Later on that summer, I bought a well-used 250cc Maico from Sills Motor Sales in Cleveland. My first official race was the “Buckeye Sweepstakes” at the Meadowlarks track and I was running second to Bud Ward in the feature race when my engine seized so tightly that it bent the connecting rod. I then bought a new 250cc Maico from Sills and I traded my first “real” motorcycle for a BSA 500cc B-33 model that I loved to race even though it was heavy and under-powered against the Gold Stars, Triumphs, Matchless, AJS and Velocettes. I would usually be in the top three and I even won a few times. As a matter of fact, I was able to beat my hero, George Singler a couple of times during the summer of ‘59. I know that one time it was at Alliance, Ohio, and I think the other time was at Mineral Ridge, Ohio. I know that both times I had trouble getting my “Big Head” into the truck when it was time to go home.

During the winter of 1959-60, Ray Sill who owned Sills Motor Sales told me at one of our CRA meetings that he was building a 650cc Triumph for scramble races ant that he wanted me to ride it. It sounded like a pretty big task, but my friend Bill Horton who was working for Ray at the time talked me into buying it. He knew it would be a good motorcycle as he had done some of the work on it. I traded the Maico in on it and took it home and put it in the utility room and began the chore of making it lighter. Ray had given me two “shorty” exhaust pipes for it and I put a moped gas tank on it. I used a BMW rear fender type of seat that I drilled a lot holes in the seat pan and removed most of the padding. Also, I bobbed the fenders, drilled centers out of shock bolts, axle bolts, and any other bolts of any size, and was able to get that monster down to 261 pounds. It was really fast and I geared it for 2nd gear starts which worked great for my weight. Counting heat races, semi-finals and finals, I raced that Triumph 36 times that summer and won 32 of them. I’m sure that I was into the first corner first all but five times out of those 36 starts. One of the wins was the “Buckeye Sweepstakes” race win that year at the Meadowlarks track in Amherst. The amazing thing about the Triumph was it’s dependability. My only work on it consisted of oil changes to the engine and one oil change to the forks, cleaning the air cleaner and spark plugs occasionally. It finally seized up at Norwalk as I was leading the last race of the year.

John Penton talked be into buying a used 175cc NSU that Norm Smith had traded in. He wanted me to try some Enduro riding in 1961. I believe that the NSU weighed about the same as my Triumph had. It was a rugged little motorcycle and I rode it on TT tracks and on Scramble tracks as well as a few Enduros. I was riding it at Smith Road Raceway in September of that year when I got my left leg all torn up by Tom Hodges’s rear wheel and sprocket and ended up in the hospital for a week. In December of that year, I rode a 75 mile enduro at Mansfield even though it was still difficult to walk. My NSU sheared the key in the automatic spark advance and luckily my friend Bill Horton came by. His big Matchless had started leaking gas, so we put my gas into his tank and he towed me to the next road because I certainly wasn’t able to push it. I only rode occasionally during the next four or five years thanks to Brown Warner and Bill Kennedy for letting me ride their BSA and Triumph respectively. I went through the Millwright Apprenticeship during this time and did not really have the time to do much racing due to a lot of overtime and going to school.

Then in March of 1966, John Penton talked me into buying a little Honda S-90. This was a time when Hare Scrambles was really coming into existence. We did some “trick” things (all legal) to the engine, lengthened the swing-arm 1 and 3/4 inches, stiffened the fork springs, installed some flat aluminum fenders and changed the handlebars and was ready to go. I rode mostly Hare Scrambles on it until the Pentons came out, but also did some Enduros and a few TT races (with knobbed tires). From April of 1966 until March of 1968, when the Penton come out, I was able to win my class over thirty times including a State Championship in 1967. Three times that little Honda won me overalls at Lagrange, Galion, and at Mansfield, Ohio on muddy tracks. I sold my trusty 90 to a friend at work in the summer after the Penton came out. His two teen-agers rode it for years until they broke the frame at a point where I had put a large hole for frame breathing. They kept riding it with the sagging frame until they finally collapsed the rear hub assembly. I sold the same man a Honda SL 125 in 1976 and he gave me back my little 90. IN 1981, I rebuilt that Honda with parts from a “parts bike”. The engine still ran great and does yet to this day. It was quite a reliable motorcycle, but when the Pentons came into existence it put my little trusty 90 into the antique class.

When the new Penton Six Day came out, I told John that I would wait until he made a 100cc so I could stay in the same class, but he insisted that I ride one of the 125s and he promised me that as soon as the 100cc engines were available that he would give me a new engine, which he did in August of that year. Anyway, I bought the very first Penton that was sold, its serial number being V003. I also had the honor of being on the first official Penton team which came about at the Berkshire Trials in Massachusetts. The team consisted of Leroy Winters, Tom Penton, Bud Green and myself. I guess that I didn’t realize it then, but I was riding with some high caliber people. I only got a bronze medal that year, but our team won the manufacturers award. That was the year that John Penton was the only gold medal winner on his Husky. I got to ride the Berkshire again in 1969 on the Penton team who again won the manufacturers award. This team consisted of Leroy Winters, Tom Penton, Doug Wilford, and myself. This time I was fortunate to be a gold medal winner. To this very day, I still have a feeling of pride for being on those first Penton teams and I am grateful to John for having confidence in me.